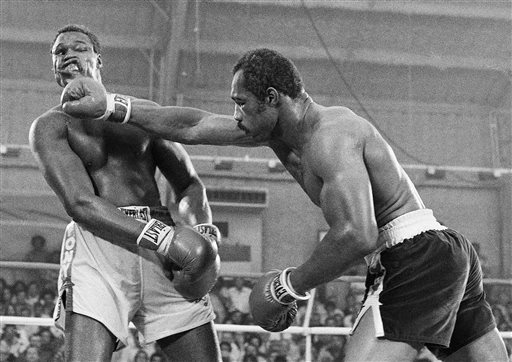

In this June 9, 1978, file photo, Ken Norton, right, and Larry Holmes battle for the WBC heavyweight championship at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Holmes won the bout in a 15-round split decision. Norton passed away Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2013, at a Las Vegas care facility, his son said. Norton was 70. Norton had been in poor health for the last several years after suffering a series of strokes, a friend of his said. Gene Kilroy, who was Ali’s former business manager, says he’s sure Norton is “in heaven now with all the great fighters.” (AP Photo/File) (AP Photo/File)

They were young once, and perhaps it’s best to remember them that way.

Magnificent men on stages equally as magnificent, they were part of the golden age of heavyweight boxing. With Muhammad Ali as the common thread, they fought in faraway places like Zaire and the Philippines, in Yankee Stadium and in the parking lot of a faux Roman palace on the Las Vegas Strip.

“On any given night all of us could beat the other,” George Foreman said. “I had Ken Norton’s number and Joe Frazier’s number. Ali had my number, and Norton had Ali’s number. No one would give up.”

For the better part of two decades, no one did. They fought each other and, if that didn’t settle things, they fought each other again. Ali in particular didn’t mind meeting a familiar foe, with three fights each against Norton and Frazier.

For Norton, who died this week at the age of 70, fighting Ali didn’t just put him in the upper echelon of heavyweights at a time when heavyweights reigned supreme. It literally put food on his table for his son, Ken Jr., who would go on to play in the NFL for 13 years and now coaches linebackers for the Seattle Seahawks.

The money was there because Ali made sure it was. He and Frazier met in what was truly the Fight of the Century in 1971, both getting $2.5 million purses that were unheard of at the time.

A few years later, Ali was heavyweight champion again, though some thought his time had passed. He hadn’t looked that great against Norton in their 1976 fight at Yankee Stadium, and now he was going to defend his title against Alfredo Evangelista, a solid if unspectacular contender most noted as being the best heavyweight ever to emerge from Uruguay.

“Why do you keep fighting?” a radio man asked Ali before the bout.

Ali looked at the man like he had just landed from outer space before explaining why he was risking his heavyweight crown.

“You know what they’re paying me for one night — $2.75 million. This is not Joe Frazier or Ken Norton or Jimmy Young,” he said. “I’m getting $2.75 million for a tuneup, a warmup, against a nobody.”

There had to be some nobodies, of course, because the heavyweights who really mattered couldn’t keep fighting each other all the time. Sometimes, though, it seemed like they did, even to those actually doing the fighting.

“They kept coming, and kept coming, one after the other,” Foreman said. “You just couldn’t find an easy target.”

Norton was no easy target — far from it. The former Marine with the sculpted body came out of nowhere to break Ali’s jaw and hand him only his second defeat in 1973. The two would fight two more times and Ali would win both, though Norton went to his grave believing that he was robbed in their last fight in 1976 in Yankee Stadium.

There was no such controversy two years earlier when Norton challenged Foreman for the heavyweight title in, of all places, Caracas, Venezuela. The fearsome Foreman, fighting one last fight before he and Ali would meet in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Zaire, knocked Norton down three times before the fight was mercifully called to an end in the second round.

“A lot of people assumed he was afraid of me but he was never afraid of me,” Foreman said. “He got in the ring and took off his robe and I looked over there and he looks like Hercules. That wasn’t pretty at all.”

Norton is gone now, never really having recovered from blows taken to the head and a car accident in the 1980s that nearly killed him. So is Frazier, and other less notable alums of the great heavyweight era like Young and Ron Lyle.

Getting hit in the head by a 200-pound (90-kilogram) man can take a toll, though some weathered it better than others. I was with Leon Spinks last year when he and his wife sat in a small room at the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas, where he was told his brain was shrinking because of the abuse it took in the ring and out.

It was grand, though now it’s not so pretty. Ali himself is nearly mute and a trembling figure these days in Arizona, ravaged by the Parkinson’s Syndrome that did what no other opponent could do — silence The Greatest.

“He’s living a more humble life now, but he’s doing good,” said Ali’s former business manager, Gene Kilroy, who visited him this year on Ali’s 71st birthday. “But he’s not the Ali he used to be when he would walk down the street and 5,000 people would follow as he yelled ‘Who’s the greatest of all time?'”

Ali was, and of that there is little doubt. He captivated the world with his mouth outside the ring, and thrilled them with his work inside the ropes. Two wins each against Frazier and Norton and mighty upsets of Foreman and Sonny Liston were more than a career for any one man.

His supporting class was awfully good too — the last batch of heavyweights to take up boxing before the lure of basketball and American football took away so many good athletes from pursuing the sport. Like Norton, they were champions too, even if Ali always seemed to reign supreme.

They were all young once, and they were magnificent.

As another one passes, we’re all lucky to be able to remember them that way.