For Ali, there were times even The Greatest wasn’t so great

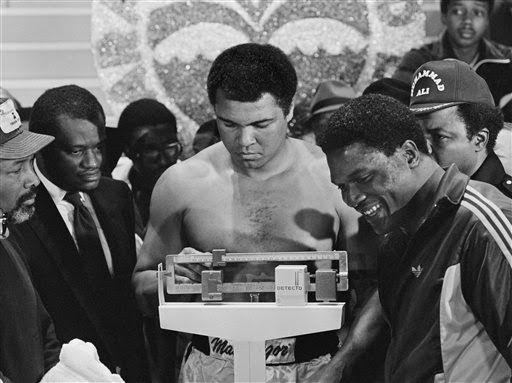

In this file photo shows Trevor Berbick, right, smiling as Muhammad Ali looks at the scale during the weigh-in for their December 11 heavyweight fight in Nassau, Bahamas. Canadian champ Berbick weighed in at 214 lbs., and Ali was 236 lbs. Ali was just a few months away from his 40th birthday when, desperate to make up for his lackluster loss the year before the Larry Holmes, went to the Bahamas for what would be his last fight. AP

He was The Greatest, and of that there is little dispute.

Muhammad Ali thrilled wherever he went, becoming the most recognized person on the planet. He showed incredible acts of kindness and moral courage, and fought almost anyone who wanted to get into the ring with him.

But there were times — some of his making, some not — when even The Greatest was not so great.

What’s my name?

It was 1965 and the world was still adjusting to the brash young heavyweight champion who scared opponents in the ring and scared a lot of Americans with his affiliation with the Black Muslims.

Ali was set to defend his heavyweight title against Floyd Patterson in Las Vegas, and Ali and his camp were upset that the former champ Patterson tried to portray himself as an All-American man who was going to regain the heavyweight crown for his country against a loudmouth Muslim. Even worse, Patterson, like many in the day, insisted on calling Ali by his birth name, Cassius Clay.

Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and the rest of the Rat Pack watched from the second row ringside as Ali came out taunting Patterson from the opening bell. He talked constantly to Patterson, saying “What’s my name?” as he beat and battered Patterson around the ring at will in a cruel display.

“It seemed as if all Clay wanted to do tonight, before 7,402 paying spectators including several movie stars, was destroy Patterson forever as a boxer and a dignified human being,” Robert Lipsyte wrote the next day in the New York Times.

The country was already divided by the Vietnam War, which was raging, and there was a big peace march in Washington the next week. The tenor of the period was reflected the day of the fight when the carrier Midway was welcomed back from the war and the mayor of San Francisco told its sailors not to pay attention to the “kooks” who were against the war.

“You should get honors and medals, the spot you was on, a good clean American boy fighting for America,” Ali told Patterson the next day. “All those movie stars behind you, they should make sure you never have to work another day of your life.”

Ali’s wife

Ali was in the Philippines in 1975, preparing for the iconic Rumble in the Jungle with Joe Frazier and was seen about town with Veronica Porsche, a woman he introduced as his wife. The only problem was, Ali had a wife back home in Chicago, and she wasn’t happy when she heard the news.

Ali and Khalilah Ali had been married since 1967 and had four children together. Khalilah promptly hopped on a plane for the Philippines, where she went directly from the airport to the presidential suite at the Manilla Hilton, where Ali was staying.

“He said on the phone that it didn’t happen and to come to the Philippines and see,” Khalilah Ali said in a 2013 interview with The Associated Press. “When I got there I found out he lied. My decision to leave him came right after that, though I promised him I’d stay until he was the 3-time heavyweight champion.”

Ali would later make Veronica the third of his four wives. He had an eye for pretty women, Khalilah Ali said, something she forced herself to tolerate.

“When he really started making money I started having problems. There were women coming out of the woodwork, always the women coming in,” she said. “When he brought them in to the house I had to make a change. Ali was very promiscuous.”

Khalilah Ali, who married Ali as a teenager, remained on friendly terms with him the rest of his life.

“I was a very fortunate young girl to travel around the world and meet kings and queens,” she said. “It was a great adventure being married to him.”

Last hurrah

Ali was just a few months away from his 40th birthday when, desperate to make up for his lackluster loss the year before the Larry Holmes, he went to the Bahamas for what would be his last fight.

The opponent was Trevor Berbick and the unlikely site was an outdoor ring at the Queen Elizabeth Sports Centre, where the card was delayed an hour because officials could not locate gloves, water or a bell. The bell was never found, and promoters ended up using a cowbell to signal the beginning and end of each round.

Ali came into the ring with a layer of fat around his waist and a somber look on his face, as if already anticipating his fate. Though the crowd hopefully chanted “Ali, Ali” as the fight began, Berbick was stronger and faster and pounded Ali for 10 rounds before being given a unanimous decision.

It was an ignominious end to a glorious career, and Ali finally admitted Father Time was his toughest opponent.

“I could feel the youth,” he said. “Age is slipping up on me.”

The words were spoken softly, with a slight slur, a portend of things yet to come.

TV whipping

Ali had a lot of affection for England, and British fans flocked to see him training in a London park before his fight there with Henry Cooper.

He had appeared several times on British talk shows, including the Eamonn Andrews Show, so it wasn’t surprising that he made a remote appearance on the show in 1968. At the time, Ali was suspended from boxing for not going in the draft and he was eager to explain why to British viewers.

“Thank you for letting me come live from Early Bird satellite,” Ali said as he sat in a U.S. television studio with an earpiece in his ear.

What came next was a public tongue lashing from American television host David Susskind, who was a guest interviewer, about his conviction for evading the draft and his refusal to serve his country in the military.

“I find nothing amusing or interesting or tolerable about this man,” Susskind said. “He’s a disgrace to his country, his race, and what he laughably describes as his profession. He’s a simplistic fool and a pawn.”

Ali had been duped, and the look on his face even from across the ocean showed it.

The wrestler

Ali was the heavyweight champion again and in search of an easy payday when he went to Japan to meet professional wrestler Antonio Inoki in a 15-round match.

Bob Arum was the promoter, and wanted to make sure nothing stood in the way of Ali’s upcoming third fight with Ken Norton. He went to wrestling promoter Vince McMahon to figure out a way to protect Ali in the ring in a promotion that would be shown on closed circuit around the United States.

“He came up with a script that was brilliant,” Arum recalled. “Ali liked it; we all liked it.”

The plan was for Ali to catch Inoki on the ropes and pound away with punches that didn’t really land. Inoki was to have hidden a razor in his mouth and cut himself so there was real blood flowing onto Ali’s white trunks.

Ali was supposed to beg the referee to stop the fight, turning his back on Inoki to make his case. At that point, Inoki was to jump on Ali’s back, taken him down and pin him for the win.

“It’s Pearl Harbor all over again!” Ali was going to yell out after the loss.

The only problem was Inoki had some handlers who thought it was going to be a real fight. For three days the two sides argued in a hotel suite about the rules for the fight, agreeing on nothing.

When the opening bell rang, Inoki raced across the ring and threw a kick at Ali, falling to the canvas. He stayed there in a crab-like position most of the 15 rounds kicking at Ali’s legs.

While Inoki wasn’t in on the plan, the referee was. He declared the fight a draw, much to the displeasure of the crowd in Tokyo.

“It was the low point of my career,” Arum said. “It was so embarrassing, just a total farce.”