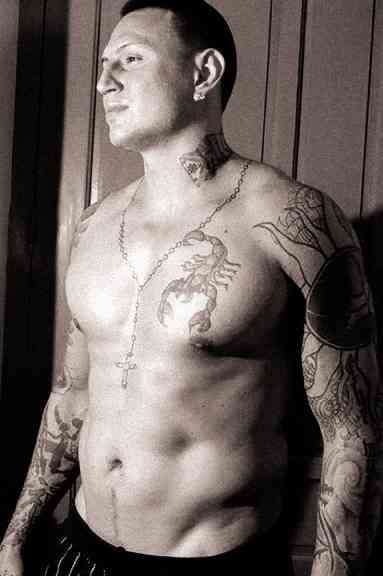

Like the proverbial book cover, you don’t judge this man’s soul by the tattoos over his body.

After all the improprieties and irreverence that marred his career as a professional basketball player a few years back, Alex Crisano now comes forward as a transformed father and civic worker.

Crisano the basketball steamroller wants to give something back to the sport that made him a popular, albeit vicious, figure on and off the 90- by 50-foot woodwork.

“I was blessed because of sports and I just want to give something back,” says Crisano, whose torso is a living canvas of his trusted tattoo artist.

The 6-foot-7 bruiser who played for PBA teams Barangay Ginebra, Talk ‘N Text, Barako Bull, Powerade and GlobalPort will soon help build a sports facility that he intends to open to young and poor Filipino athletes, his “modest contribution” to the country’s grassroots sports development program.

Crisano, now 40, admits he also draws inspiration from the feat of weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz, who won a silver medal in the recent Rio Olympics.

“I did a lot of nasty things, but it’s all in the past,” says the still fighting-fit Filipino-American, who wound up his PBA career in 2013 with GlobalPort with averages of five points and four rebounds a game. “I’m a changed man and I’m willing to create change through sports.”

The hulking 240-pound center-power forward began his playing career in the country with the Nueva Ecija Patriots in the now-defunct Metropolitan Basketball Association in 1999.

A year later, Crisano signed up for the Ginebra Gin Kings, kicking off a tumultuous PBA career that spanned 14 seasons. He won a championship alongside Marc Caguioa, Jay-Jay Helterbrand and the rest of the fabulous Kings in the 2008 season.

But along the way, Crisano figured in memorable on-court fights and flagrant fouls, making him a certified villain in the eyes of Ginebra’s opponents.

He would strike a pose a la Hercules or the alpha-gorilla whenever he scored on a dunk, according to Willie Marcial, the PBA’s media bureau chief.

“He was mean and funny at the same time,” says Marcial, recalling Crisano’s years in the league. “Woe unto the player who strikes him with impunity.”

Crisano incurred suspensions and hundreds of thousands of pesos in fines levied by the PBA Commissioner’s Office.

“I’m passionate with what I do,” he says. “It became intense out there because of my love for the game. That’s how I give my 100 percent on the court.”

Crisano once unsuccessfully tried out for the national boxing team. He now customizes cars for a hobby.

Life, however, isn’t always rosy for the former cager who grew up in Brooklyn, New York.

Pilloried on social media for his transgressions outside the court, Crisano’s playing star faded as he grew older.

A few years back, Crisano’s car exploded for a still unknown reason, triggering a fire in the car park of a posh condominium in Eastwood, Quezon City.

A fractured marriage and several failed relationships, including an ugly breakup with comedienne Ethel Booba, made him a sizzling gossip-page item.

During an exhibition game inside a military camp, a witness recalled how a player who looked very much like Crisano pulled down his shorts in front of a popular female newscaster who tried to interview him.

Looking back, Crisano says he learned to be sober while watching his five kids grow up.

“I guess the reason for my maturity are my children,” he says. “I want to be a better person for them.”

One of the five is Alex Jr., a 16-year-old, 6-foot-2 shooting guard.

Mean as he was, Crisano was among the first players to answer the PBA’s call for help when the league sent a team to help the victims of Supertyphoon “Yolanda” in Leyte in 2013.

A self-appointed basketball ambassador nowadays, he never fails to inspire whenever he plays pick-up games across the country. On the side, he teaches kids the game’s fundamentals.

Crisano says he attracts positive energy by doing good and sharing his blessings.

For now, he busies himself looking for a place in Taguig City to build his training center, which will have a basketball court, a football field and space for other sports.

“The funds will come from my own pocket, with help from my partners,” Crisano says. “It’s my way of saying ‘Thank you’ for the things that sports has done for me.”