In an era a long, long time ago, Filipino tenpin bowlers were rock stars.

It was a time when a tall and dashing mestizo, Paeng Nepomuceno, loomed large as the sport’s poster boy, an era when queues of youngsters wanting to be trained by the local masters were long and the bowling centers were the “in” places to be.

Nepomuceno, Bong Coo, Lita dela Rosa, Arianne Cerdeña, Bec Watanabe and Ollie Ongtawco left for overseas competitions one after the other and came back home with world or continental titles.

Theirs was an unparalleled two-decade (1976-1996) victory parade that made them household names, adored like the land’s basketball superstars.

Filipino bowlers crowded the Americans as the finest in the world, and the 6-foot-2 Nepomuceno exemplified the country’s preeminence with four World Cup victories, three of them coming in different decades.

But bowling’s halcyon days slowly came to an end as a series of leadership disputes and a lack of sustainable development in the sport, according to two former national team stalwarts, created thick cobwebs that smothered the sport for protracted periods.

Victories later came far and between. Christian Jan Suarez claimed the 2003 World Cup in Tegucigalpa, Honduras; Liza del Rosario, Liza Clutario and Cecilia Yap ruled the women’s trio in the FIQ World Tenpin Bowling Championships in Kuala Lumpur in the same year, and Biboy Rivera seized the Masters title in both the FIQ championships in Busan, South Korea, and the 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games. Disappointingly, nothing followed these feats.

Last year, the depths into which the country’s hopes in bowling had slipped was magnified when Filipinos managed just two bronze medals in the 10-event Southeast Asian Games competition in Singapore. Thirty-eight years after swashbuckling Filipino bowlers grabbed seven of the eight golds disputed in the 1977 edition of the Games (they settled for the silver in the eighth event), Philippine bowling finally came to grief.

“In the 1970s and ’80s, we were next to basketball in terms of popularity,” said Philippine Bowling Federation (PBF) president Steve Hontiveros. “It breaks the heart that it’s no longer the case now. We need to make up for the lean years by making the sport stronger again.”

What caused this monumental decline?

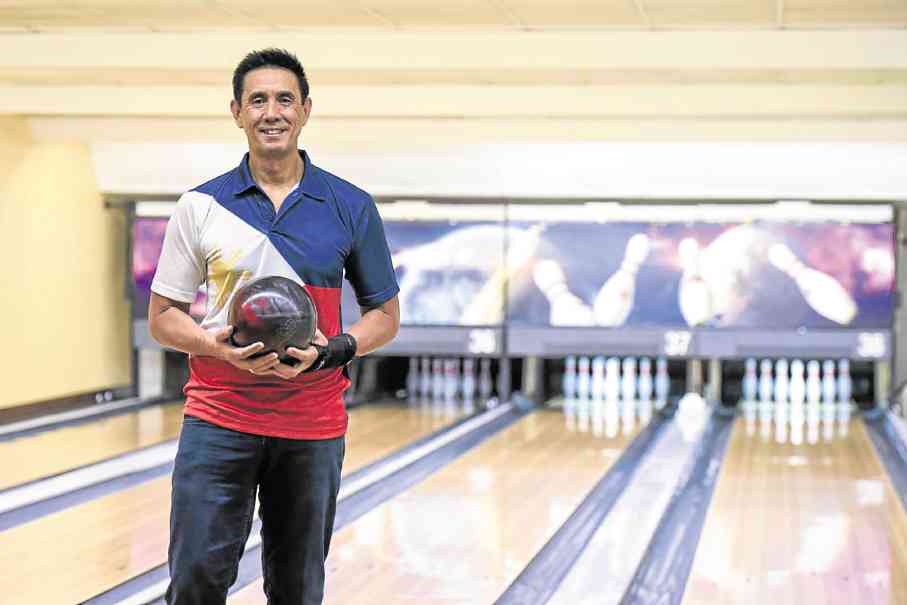

“Technology; the game has changed,” says the legendary Nepomuceno, who won the World Cup as a 19-year-old in 1976 in Tehran and then in 1980 in Jakarta, 1992 in Le Mans, France; and 1996 in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

“Science and technology took over and we were left behind technology-wise. These days you need to match your ball with the bowling lane, for example. If you don’t know how to match them, you’re already at a disadvantage. During our time, it took pure talent to curve a ball. Now the ball can do it for you.

“Times have also changed training-wise. We used to train all day because we were full-time athletes,” adds the 59-year-old Nepomuceno. “Now the bowlers train only in the evening, after office hours.”

To help stop the malady, the PBF has tapped Nepomuceno as head coach of the national men’s and women’s teams. With him in the coaching staff are top-notch players themselves: United States Bowling Congress (USBC)-certified coaches Rivera and Jojo Canare, as well as Rey Reyes and Johnson Cheng.

Considered the greatest bowler of all time, Nepomuceno is actually following in the footsteps of his late beloved father-coach Angel, who guided his son to the bulk of his 130-plus national and international titles—one of three Guinness Book of World Record entries attributed to Nepomuceno. He is also cited for being the youngest World Cup winner at 19 and for his four victories in all.

The big decline in the number of major tournaments also contributed to the paralysis, says Nepomuceno, an international bowling Hall of Famer like Coo and Dela Rosa, who is armed with the prestigious “Gold Coach” certification from the USBC.

“You get better when you compete in tournaments,” says Nepomuceno. “These days the bowlers do not have the luxury of choosing tournaments to play in simply because there is a lack of big tournaments in the first place.”

Adds Hontiveros: “Many bowling centers have closed and the remaining few still in operation, like the bowling clubs, are hard-pressed to come up with tournaments. It’s difficult to put up money for such events.”

Hontiveros recalls how players from Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, among other countries in the Middle East, used to come over to train alongside their Filipino idols. Filipino bowling coaches snagged top-paying jobs in the Middle East, one of them national mentor Toti Lopa, who was hired to coach the UAE national team.

“These days the Qataris and the UAE players are among the best in the world,” says Hontiveros, the president of FIQ (the French acronym for International Tenpin Bowling Federation) from 1992 to 1997 and for more than two decades the head of the Philippine Bowling Congress, the PBF’s predecessor, until he stepped down in 2000. “We were left behind because the rest have all the equipment and the motivation to play very well.”

Early this year, with the PBF in its most serious state of disarray, Philippine Olympic Committee president Jose Cojuangco Jr. stepped in and urged Hontiveros to lead efforts to “essentially build a new bowling federation.”

With the blessings of the World Tenpin Bowling Association (formerly FIQ), Hontiveros gathered all the sport’s stakeholders. With the appointment of Sen. Vicente “Tito” Sotto, himself a former World Cupper, as PBF chair, the group drew up a new list of members and drafted a new charter. The 59-year-old Nepomuceno gave the initiative a massive boost by offering to become the national team’s head coach.

“We have set up a new organization and are developing the grassroots,” says PBF secretary general Alex Lim. “We are seeing a lot of potentials, even in the provinces.”

Nepomuceno says they will hold eliminations to choose the members of the national pool in November. From that pool they will form the six-man, six-woman PH teams that will compete in the World Combined Championships in Kuwait for the first time after three failed attempts at qualification.

“My initial work is to craft the National Bowling Pool Training Program,” he says. “It is focused on the bowlers’ physical game, lane play, understanding of equipment, strength and conditioning, nutrition, and most importantly, mental preparation. It involves several training modules incorporated into the national pool’s training and competition calendar.”

Nepomuceno says the golden age of bowling from the mid-1970s to mid-’90s will always be an unforgettable part of the country’s sports history.

“The process of reviving that era is definitely arduous but we are certain that our aggressive and consistent effort will put the sport back to where it was once was,” he said.

With Nepomuceno rolling the first ball, the pins loom large for Philippine bowling’s long-awaited comeback.