As he stepped up to the plate one last time, Filomeno “Boy” Codiñera knew he had done well for his teams, country and family to take all of his happy memories to his next field of dreams.

The final out was coming, he could feel it, but he was ready to strike out swinging. After suffering two strokes that robbed him of his ability to function normally, he had no fear anymore of the pitch that would end it all.

And so when it came in the wee hours of the morning of Oct. 26, the greatest softball and baseball player to don the Philippine jersey passed away peacefully.

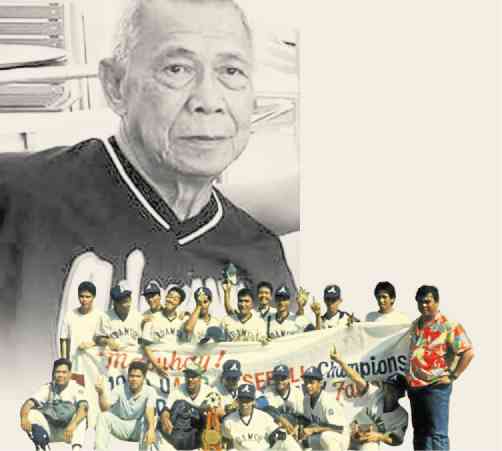

Codiñera—he was 77—left a lasting legacy in Philippine sports. In no small way, the fearsome slugger from Guadalupe, Cebu, also left a legacy in basketball, in the form of three equally tall sons who played for the national team and in the PBA.

For over two decades, the 6-foot-2 Codiñera was a towering figure in softball’s outfield as well as an accomplished home run stalwart. His one brilliant feat of slugging merited an entry in the Guinness World Records.

Codiñera, a terror on third base in baseball, was many things to many people: a top-notch player for the national team; father to PBA great Jerry and his siblings, former fellow pros Harmon and Pat; a decorated police officer with “Manila’s Finest.”

In 1968, he set a milestone while playing for the Philippine Blu Boys during the World Softball Championship in Oklahoma City. In a single game, he blasted seven consecutive doubles, earning him a place in the Guinness book.

Codiñera helped the country win the bronze medal in the 1966 World Amateur Baseball Championship in Hawaii and, in 1972, famously belted a grand slam home run at full count (three balls and two strikes) in the 10th inning of the Philippines’ final game against Mexico as the Blu Boys prevailed, 6-2, and finished fifth in the World Men’s Softball Championship held in Marikina.

But little is said about this beloved and respected, albeit strict, mentor. Friends and the coach’s students say “Mang Boy” never realized how much he had influenced the present generation of coaches.

“All of the coaches out there won’t be where they are now if not for Coach Boy,” said Randy Dizer, a former Blu Boy and now Ateneo’s softball-baseball program director. “We emulated him. The very competitive methods I use to train my players at Ateneo, I got all of them from him.”

Dizer was part of the crack Traders Royal Bank squad that ruled the Philippine Baseball League back in the 1980s, when Codiñera was the team’s playing-coach and then its full-time mentor.

Codiñera was so strict with his players, Dizer ventured that the legendary baller’s sons “probably worked hard to become basketball players.”

Jerry confirms Codiñera’s almost boot-camp way to instil discipline.

“It’s like we had a phobia having him as coach,” he says. “He’d tell us ‘You’re not blind, you can see the baseball, you can see the (basketball) ring, then why can’t you hit it or shoot the ball?’

“Sometimes I tell him, he’s stricter with his sons than with his players,” adds Jerry, who started in Little League baseball as an eight-year-old.

A teammate of Harmon in Far Eastern University’s softball squad, Dizer saw how Codiñera avoided favoritism. “He would make Harmon run plays with (workout) irons on his legs,” he recalls.

Delia Pablo, a former right fielder for the Blu Girls who now works as Mapeh (music, arts and physical education, health) teacher in Rodriguez, Rizal, recalls how Codiñera held regular “recitations” of softball terms for the team.

“It was very important to him that we knew the rules, so he conducted impromptu lectures,” says Pablo of his coach, who was always ready to discuss the sport’s terminologies with members of the Philippine Sportswriters Association (PSA) who covered the games.

One day, after a specially tiring workout, Codiñera asked the Blu Girls what “fair fly ball” means.

“One of my teammates nervously offered an answer but pronounced the term as ‘fair fly boy,’” says Pablo, now 58. “It elicited laughter among the Blu Girls but made Coach Boy cringe.

“He was a disciplinarian because he wanted to challenge you.”

Former Blu Boy Orlando Binarao, who won four UAAP softball titles in five years for Adamson under Codiñera’s watch, says their former coach squeezed everything in his players to make the team strong.

“He managed to harness our talents to the hilt because of his sternness,” says the 47-year-old Binarao, now Adamson’s softball-baseball coach. “He always reminded us that since we chose the sport, we might as well work hard to be good at it.”

Now a coach at Arellano University in the NCAA, Jerry says his father didn’t believe that games are influenced by luck: “He said that games are won by 99-percent preparation. He often reminded us, ‘If you rely on luck, then just go to church every day.’”

Among the many important aspects of the game, Codiñera focused on stamina and endurance. “Whenever he produced his baton, that meant we were up for a one-mile speed run,” says Pablo.

Codiñera’s eldest grandchild Nicky, who played basketball for Adamson, recalls how strict her Papa Boy was when it came to physical fitness.

“He was very concerned about what we ate and how we exercised because we were athletes,” says Nicky, the 31-year-old daughter Codiñera’s eldest, Harmon. “It’s like he was still a police officer, even in old age. Papa Boy was a disciplinarian but he was very loving to all of his grandchildren.”

Codiñera the coach, friend and patriarch may have passed away, but his legacy will live on in the minds and hearts of those whose lives he touched.

He was survived by his wife Beatriz and sons Jerry, Harmon and Pat and only daughter Pamela. His cremated remains will be interred today at Adamson Columbarium.