Juego Todo opens with a battle of sticks and kicks with the fighters wear head gears. By the final round, it becomes

a showcase of different local fighting styles.

As the sound of clattering sticks fills the air, the fighter finds an opening, his wooden weapon slaps on his opponent’s bare back flesh, leaving a red, blotchy streak.

“May mga latay na sila! (They have whip marks),” the barker hollers. “Masakit ito! (This is painful).”

The bell rings in the next round. All weapons down, the fighters unleash a flurry of kicks and punches. They grapple, get tangled in locks and chokes amid faint grunts. The crowd cheers.

Welcome to the world of Juego Todo. To the uninitiated, it may be well like fraternity hazing with the trappings of combat sport.

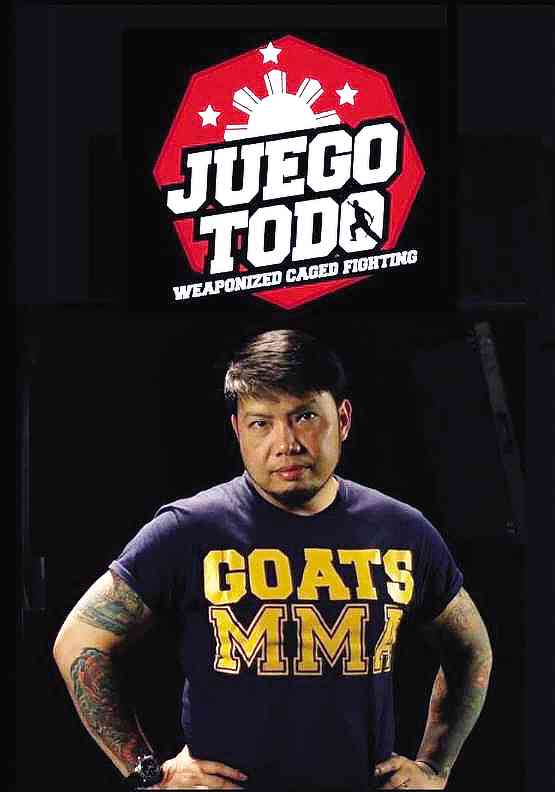

“It’s not fully accepted yet because for the purist—we’re being criticized—it’s too brutal; there’s no respect,” says Ferdinand Abadilla Munsayac, the founder and chief executive officer of Underground Battle Mixed Martial Arts (UGB MMA).

“All I have to say to everyone who criticizes what we do, one word—evolution. They all have to accept change. Without change, we’re not moving forward.”

There’s a level of masochism or even craziness, as some may say, needed to go full action in this sport. But for Munsayac and his fighters, it’s their way of bringing Filipino martial arts (FMA) to the mainstream.

“Juego Todo was born because I saw FMA is so good,” says Munsayac. “Arnis is so great it’s adopted in Hollywood fight scenes, it’s adopted in elite forces in the military. But look here locally, where are they? You see them in the parks. When they have something official, they’re in a basketball gym. There’s no prestige. So putting these world-class fighters inside the cage and showcasing what they have, this is it.”

Juego Todo opens with a battle of sticks and kicks. The fighters wear head gears, but no body armor. It’s like arnis with two sticks, but they get to sneak in kicks.

It’s “weaponized cage fighting,” as Munsayac puts it. Featuring three rounds of three minutes each, the fight closes with full-contact striking and grappling inside a cage known in the MMA as an octagon.

“In the second round—if they last—they fight with a single stick,” says Munsayac. “They can deliver kicks, they can use their elbows, punch with the empty hand. Any given time a fighter gets disarmed and your opponent still has a weapon, you just have to keep fighting.”

By the final round, all gears and weapons are dropped, and it becomes a showcase of different local fighting styles—sikaran (kicking techniques), buno (Filipino-style wrestling), panuntukan (punching techniques), dumog (Filipino-style grappling) and yaw-yan (Filipino-style kickboxing).

A fighter can win on points, by submission, by knockout or technical knockout.

“[The sport is] a hybrid of Filipino martial arts,” says Munsayac. “It’s like bringing in the modern-day Pinoy gladiators, the arnisadors, and putting them in the modern-day arena, which is the cage.”

A former United States Navy chief petty officer, Munsayac has always had the affinity for reality combat. So when he decided to return to his roots and retire in the Philippines after 20 years of military service, putting up a gym and a promotion outfit became his focus.

Munsayac opened The Goat Locker Boxing Gym, which also offers muay thai, mixed martial arts and arnis, over five years ago. He later launched a new platform for amateur fighters before they plunge into professional leagues—the Underground Battle MMA. Shady as the name sounds, it’s an official licensee of the World Series of Fighting Global Championship.

It’s also in this outfit where Juego Todo—which translates to “I play all” in Spanish—was born.

“After being able to establish [the promotion outfit] after two years, I thought about some people who were left out, and those were the FMAers (Filipino martial artists),” says Munsayac. “So we thought of coming out with something different, but not much different because they’re already doing it.”

Right now, Juego Todo gets to “piggyback with our MMA fights,” because as Munsayac puts it, “We’re still at the infancy stage of this league.”

But Munsayac wants to cut through demographics, so the burly promoter has been staging fights all over the country, from the Benguet hills to Taguig City’s posh McKinley Hill.

“We bring MMA to the fans out there,” says Munsayac. “We’re the type of promotion that does MMA by the beach, by the cemetery, in the mall, in the red-light district area, the first in all major provinces. That’s what UGB MMA does.”

But it’s a rough sport with a soft spot. Munsayac’s group has also been providing scholarships to talented but underprivileged fighters. “We have a fighter advocacy and that’s the main reason we exist today,” he says. “This fight promotion is about helping the less fortunate fighters.

“We offer free lodging, free training” adds Munsayac. “We provide proper training for them to become fighters and compete. We provide them shelter, a few scholars stay in the gym, and in exchange, they help clean the gym.”

In a few days, these new breed of fighters will go at it again. And as they make their way to the Octagon, there will again be the fight’s catchy rap on heavy rotation: “Handa ka na ba sa basagan? Handa ka na ba sabugan? Panahon na para magkaalaman, kung sino ang hari ng wasakan! (Are you ready for the brawl? Are you ready for the explosion? It’s time to know who’s the king of destruction).”

Definitely the kind of pump-up song any Juego Todo fighter would need.