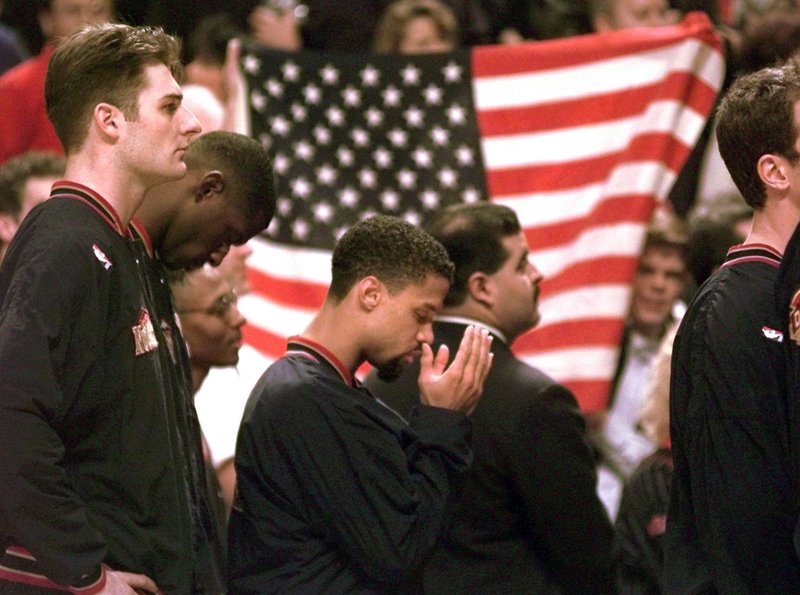

FILE – In this March 15, 1996, file photo, Denver Nuggets guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf stands with his teammates and prays during the national anthem before the game with the Chicago Bulls in Chicago. During the 1995-96 season, Abdul-Rauf began stretching or staying in the locker room during the national anthem. He was suspended for one game. But at season’s end, despite averaging 19.2 points and 6.8 assists, he was traded from the Nuggets to the Sacramento Kings. And when his contract expired two years later, he couldn’t get a tryout and was out of the league at age 29. (AP Photo/Michael S. Green, File)

By the 1980s, America finally publicly embraced the black athlete, looking past skin color to see athleticism and skill, rewarding stars with multimillion-dollar athletic contracts, movie deals, lucrative shoe endorsements and mansions in all-white enclaves.

Who didn’t want to be like Mike?

But those fortunate black athletes like Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods did not, for the most part, use their celebrity to speak out. Most were silent on issues like the crack epidemic, apartheid in South Africa, the racial tensions exposed by the O.J. Simpson trial and the police brutality that set off the Rodney King riots.

Of course, there were exceptions — more, perhaps, than are generally remembered. And the times and the media of those times did not necessarily lend themselves to protest. But while Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali once stood up— and more recently, Colin Kaepernick , Lebron James, Serena Williams and others would not back down — black athletes of the ’80s and ’90s were known mostly for playing games.

“It seems to me that we need to rethink how we define ‘activism’ since black athletes certainly were involved in various social causes during that era. Anecdotally, I think about them donating to various scholarship funds and participating in ’say no to drugs” campaigns,’” said Johnny Smith, who is the Julius C. “Bud” Shaw Professor of Sports, Society, and Technology at Georgia Tech. “That’s certainly a form of activism. However, on the whole, the most prominent black male athletes were not confrontational or outspoken.”

When Harvey Gantt took on conservative Republican Sen. Jesse Helms in 1990, Jordan — the undisputed superstar athlete of his time — refused to support the black Democrat in his native North Carolina, reportedly saying Republicans buy shoes, too.

It took until 2016 for Jordan to finally speak out strongly on a social issue by condemning the killing of black men at the hands of police, writing in a column published by The Undefeated website.

Woods said this week that throughout America’s history, blacks have struggled.

“A lot of different races have had struggles, and obviously the African Americans here in this country have had their share of struggles,” Woods said. “Obviously has it gotten better, yes, but I still think there’s room for more improvement.”

The mold of the public activist — the person who is willing to lead but also willing to lose everything for a cause — doesn’t fit everyone, said Harry Edwards, a scholar of race and sports who has worked as a consultant for several U.S. pro teams.

Some guys are fine “picking up a paycheck” because they don’t want to be bothered, Edwards said.

“But that’s fine, because that has always been there,” he said. “That was there during slavery. Nat Turner comes and says, ‘Hey, let’s run away. Let’s get some guns. Let’s get some machetes, and let’s fight for our freedom.’ And you always have someone say, ‘You kidding me?’”

Dominique Wilkins, an NBA Hall of Famer known as the “Human Highlight Film” for his thunderous, acrobatic dunks during the 1980s and ‘90s, believes social media have amplified athletes’ voices — and the Twitter-less past did not offer sports stars the soap boxes they have now.

“We didn’t have a platform because it wasn’t that type of media around,” Wilkins said. “You had the normal, everyday media, but you didn’t have Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, you didn’t have any of that.”

Wilkins, 58, said people are completely off base when they say his generation didn’t do anything or care about what was happening in their communities and in the world.

“We grew up in a different era. We were born in the civil rights era. I remember when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated,” said Wilkins, an NBA analyst for Atlanta Hawks games for Fox SportsSouth. “People who say we didn’t care don’t know what they’re talking about. … We cared. We were a part of it, so we cared.

“Our parents lived it. Our grandparents lived it. How can we not care?”

The activism of the time was different, said sports historian Victoria Jackson, who works in the School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies at Arizona State University.

Behind the scenes, superstar athletes worked in their communities and with schools — without making their activities known or asking for publicity for their time. Millions of dollars went to schools like historically black colleges and universities — as well as other deserving charities including social justice charities — without public acknowledgment, Jackson said.

“While we might have seen a decline in athletes voicing strong opinions publicly about systemic racism, police brutality, criminal justice and education and residential and workplace reform, and perhaps the growth of endorsements contributed to this, I would suspect — if we did a little digging — we’d find countless stories of athletes doing work in the space of social justice and that this is the constant theme in the long historical arc,” she said.

There were some who spoke loudly. A dashiki-wearing point guard Craig Hodges, Jordan’s teammate on the Chicago Bulls, presented then-President George H. W. Bush with a letter in 1991, urging more concern for African-Americans during one of the Bulls’ championship trips to the White House.

During the 1995-96 season, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf began stretching or staying in the locker room during the national anthem. Abdul-Rauf was suspended for one game. But at season’s end, despite averaging 19.2 points and 6.8 assists, he was traded from the Denver Nuggets to the Sacramento Kings. And when his contract expired two years later, he couldn’t get a tryout and was out of the league at age 29.

Those protests, some say, may not represent the most radical actions of black athletes of the time, which were in the boardrooms, not on the streets.

Jordan built a brand that turned him into a Nike powerhouse, where he brought African-American businessmen and women up the ladder with him, before becoming the first black sports billionaire with his NBA team ownership of the Charlotte Hornets.

Magic Johnson, in addition to building a business empire, spoke out passionately about the HIV/AIDS crisis after contracting the disease. The NFL’s Man of the Year award was long named for Walter Payton, who pushed organ donation into the public limelight in his native Chicago and around the country through his foundation while advocating for minority ownership in professional football.

Mike Glenn, a 10-year NBA veteran who played from 1977-87 and member of the National Basketball Retired Players Association board of directors, believes how those first black millionaires went about their business helped build the foundation that allows athletes to speak out today.

“I think all of them were aware of backlash,” said Glenn, a collector of documents on African American history and culture . “They were aware that if you say certain things it may hurt your brand, or may hurt your ability to do things or that maybe even the league would take a different look at you. I think it was an insecurity of their position regardless of how much success they had.”

Jordan and other iconic athletes of that period established the power of individual sports brands, a transitional platform Glenn believes athletes benefit from today.

“LeBron has took what Michael had,” Glenn said, “and taken it a step further.”