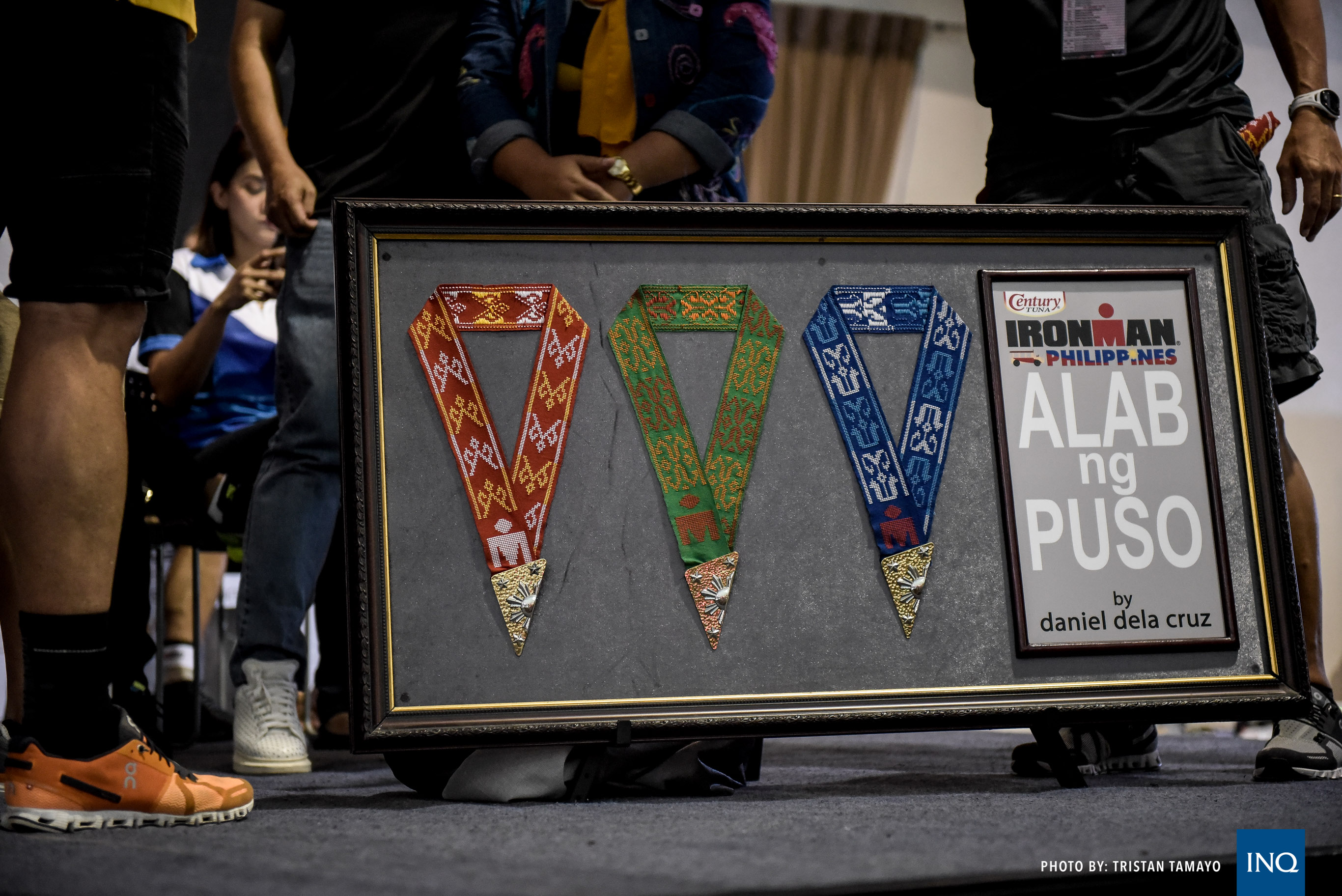

ALAB NG PUSO. These specially handcrafted medals and ribbons from Marawi weavers will be one of the prizes for the finishers of the first Ironman race in the Philippines.

A reward like no other awaits finishers of the first full-distance Ironman race in the Philippines.

Each participant who completes the arduous 3.8-kilometer swim, 180 km bike and 42 km run earns a special medal that not only symbolizes victory but also signifies the Filipino spirit and the sport of triathlon.

The commemorative piece was created by Daniel dela Cruz, a renowned Filipino metal sculptor.

“The title of the medal is ‘Alab ng Puso’ and it’s the fire in the heart which I think each and every triathlete needs to be able to finish the race,” said Dela Cruz.

But a medal won’t be one without a ribbon and making it was no easy task either.

Staying true to the Filipino theme, each sling was made by weavers from war-torn Marawi.

Weaving has been a cultural tradition in Marawi but the Maranaoans have been struggling to keep it alive through the changing times especially when the city came under siege in May of last year that lasted for nearly five months.

During the war, lives, homes and livelihood were lost. In the aftermath, bombed-out buildings, rubble from destroyed establishments and bullet-punctured walls describing a city in tatters are those left of Marawi.

But amid adversities, hope, perseverance and the fight to revive the true identity of the Maranaoan and their culture remained.

“First, we wanted to do this to help the weavers, but we were shocked to learn that our equipment were destroyed. We encountered a lot of other challenges but I kept telling them this is going to be one of those that will prove that we can get back to our feet,” said Salika Maguindanao-Samad in Filipino, who, along with her husband Jardin, led the efforts in making the ribbons. “We were inspired and thankful because this is also our livelihood before that has somehow been forgotten but now, it’s giving us hope.”

“We encouraged them to bring back weaving because that is something that we can be proud of and not be known for all the wrong reasons of being labeled as terrorists. We want to show that we are known for something much bigger than that and that we have a culture,” said Jardin in Filipino. “That’s what we want the world to know about us.”

More than 50 weavers overcame the odds and spent countless hours to make more than 1,200 ribbons in less than four months.

The couple hopes that this is just the start of something even bigger in store for the Marawi weavers and their families.

“For us, it was really our advocacy to make it sustainable. The reason why this is dying is because a lot of weavers stopped working because it’s not sustainable in helping them and their families and that’s a big challenge for us. How to make it sustainable livelihood for them especially with the fact that we had to start again from the ground up,” said Salika.

Jardin lived in an area most affected by the war. He had nothing left of his home after it burned down.

“Weaving those ribbons was a big help to us because when we accepted the job, the pain was still fresh in each and everyone of us here in Marawi,” he said.