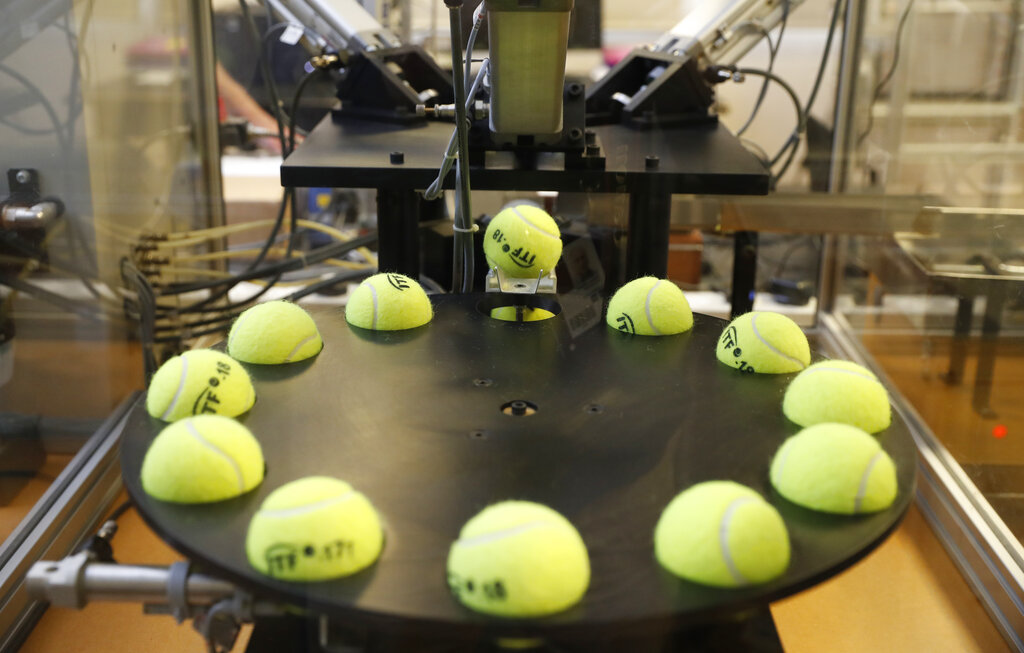

In this photo taken Friday June, 28, 2019, a tennis balls are lined up to squashed by pistons as they are tested by the International Tennis Federation (ITF) lab in Roehampton, near Wimbledon south west London. Based for about 20 years in a three-room area on what used to be a pair of squash courts in Roehampton, the ITF tech lab is filled with more than $1 million worth of machines that help make sure rules are followed and parameters are met. (AP Photo/Alastair Grant)

WIMBLEDON, England — Roger Federer isn’t entirely sure whether it’s the grass courts themselves or the tennis balls or what, exactly, but he does know this: Something feels slower about the way Wimbledon is playing nowadays.

Federer’s semifinal opponent Friday, Rafael Nadal, disagrees, saying the courts feel the same to him as they have since he first played at the tournament in 2003.

“Personal feeling,” Nadal said. “Personal opinion.”

Here’s who really knows the answer: The folks at the International Tennis Federation whose job it is to test and approve courts, balls and other equipment for tournaments around the world. Based for about 20 years in a three-room area on what used to be a pair of squash courts 3 miles away in Roehampton, the ITF tech lab is filled with more than $1 million worth of machines that help make sure rules are followed and parameters are met.

There’s a serve-simulating robot arm nicknamed “Myo,” from the Greek word for “muscle.” There’s a wind tunnel that roars at more than 150 mph. It’s also where the portable contraptions used to measure court speeds were developed and refined — the very ones brought out to the All England Club last month to check each playing surface, just like every year before the likes of Federer and Nadal begin play.

So … ?

“We are not able to disclose the results,” said Jamie Caple-Davies, the head of the ITF’s science and technical department, “as these are provided to the (club) in confidence.”

Hmmmm.

Asked whether the pace has slowed over the years, Neil Stubley, head of courts and horticulture at the All England Club, said: “I’m sure it has, but I think players’ styles probably contribute to that, as well.”

“Probably racket technology, string technology, how players can manipulate the ball more, all has a factor,” Stubley added — and he didn’t even mention other elements such as temperature or humidity that can play a role.

All of that, and more, is precisely the sort of area that Caple-Davies, two full-time colleagues and an intern explore.

“We monitor the state of the game and how is tennis being played, characterize the equipment that’s being used and then look at how that equipment affects how the game is being played,” Capel-Davies said.

They make sure hard courts used for Davis Cup and Fed Cup matches meet regulations (countries have been fined and docked ranking points for using surfaces that were too fast or too slow).

They try to assess how changes in the game are happening over time, often collaborating on studies with Ph.D. candidates at British universities.

For Wimbledon and other tournaments, line-calling technology is tested. So are thousands of tennis balls, to ensure the weight, size, bounce height and durability are proper.

Just like any ball manufacturer seeking a stamp of approval for its product, Slazenger, a Wimbledon sponsor since 1902, sends 72 balls to Capel-Davies’ lab about nine months before the tournament begins. Of those, 24 get checked; 23 must pass muster. Then the same tests are run on 24 balls the lab gets while the tournament is in progress.

Used to be that the balls sold three-to-a-can in stores for recreational play were quite different from those used in tournaments.

“Now the ones in the market are much closer to the submitted ones than they’ve ever been,” Capel-Davies said. “There’s hardly any gap now.”

Part of what he and his crew are up to is attempting to understand the game, at both an elite and recreational level. So they’re sussing out how changes in equipment — yes, balls and rackets, but also shoes, say — change the sport and monitoring whether adjustments to the rules could be needed.

They look at how balls are altered as a match goes on. How strings wear. What surfaces might be better for local clubs to use, depending on what their players’ level is.

The lab is also where the future of the sport is taking shape, including something right at the cutting edge now: player analysis technology, which has yet to take off on tour but would seem to be the next logical step in this increasingly data-driven age.

“One of the things that we’re trying to do is ensure that tennis is appealing for both players and spectators — that it doesn’t sort of become a shootout, a fairly one-dimensional sport that only certain kinds of styles really benefit from,” Caple-Davies said. “So that has maybe curtailed some of the very fast surfaces … and certainly in our team competitions, something that the ITF is taking some action to mitigate against.”

They take submissions from anyone who believes they have the perfect new way to make a racket, or string one, to determine whether the newfangled idea is within the rules.

Applications come from all over the world.

“That starts normally with an e-mail of some sort of concept of what they’re thinking of or what they’ve invented. And then we typically request a prototype so we can make a judgment or refer it to our technical commission to make a decision on whether it conforms or not,” Capel-Davis said. “Or whether we need to actually look at the rules more closely and potentially even amend the rules to deal with this innovation.”

He’s aware, certainly, that the technology and science he oversees can push the game forward.

But he also knows Wimbledon dates to the 1870s and that tennis is as tied to its considerable past as any sport.

“We want to try and maintain the traditions of the sport … so if somebody who’d been watching it 150 years ago had access to TV or went to an event, they would be able to recognize it as that sport,” Capel-Davies said. “But that does not mean that it will be identical. And so we are trying to create an environment where there is the possibility to innovate and to bring technology into the sport for a positive outcome.”