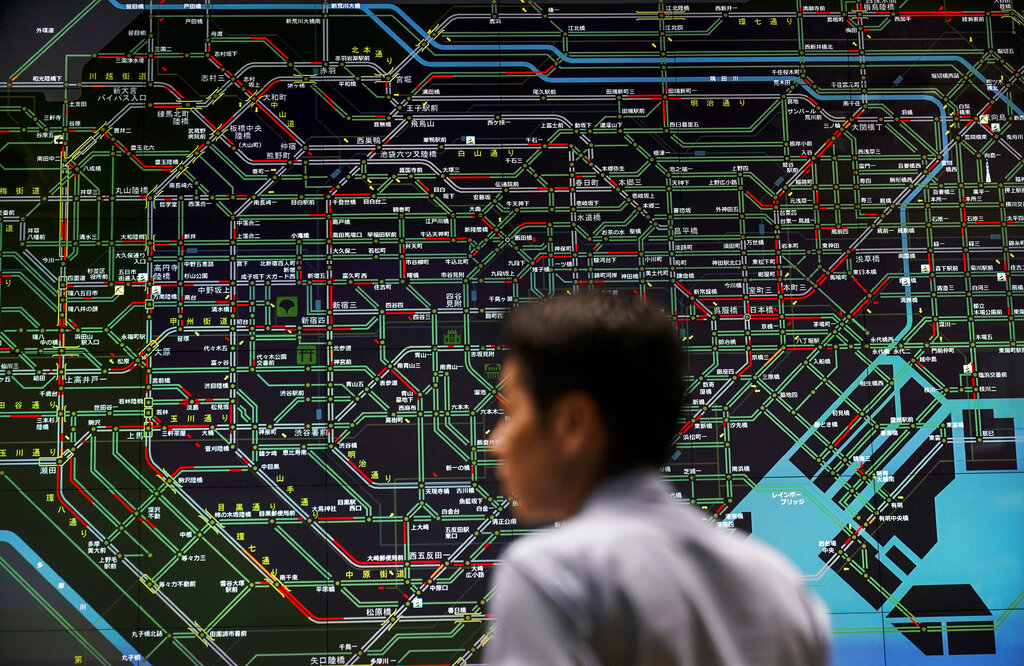

In this July 26, 2019, photo, an officer monitors the flow of public transportation in front of a screen showing Tokyo’s web of train lines at the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department’s traffic control center in Tokyo. Tokyo has one of the most advanced public transport systems in the world, but with less than one year to go before the city hosts the 2020 Olympic Games, local governments, companies and commuters are bracing for unprecedented strain the events could put on rail transit and highways. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

TOKYO — First, Tokyo Olympic fans will have to find scarce tickets and pay the price. Then there’s the quandary of landing a hotel room with rates that are being inflated due to unprecedented demand. And the summer heat and humidity will be off-putting for some.

Then there’s one more hurdle: getting around, or even finding a tiny space to stand on Tokyo’s famously efficient but over-stressed rail system.

Japanese professor Azuma Taguchi at Chuo University has researched Tokyo’s system for years and says it’s already running at double its capacity and the Olympic crunch could push it to the breaking point.

“When peak capacity is twice or three times above normal, it’s possible some people could be killed,” Taguchi told The Associated Press.

His computer simulation predicts that the biggest wave of Olympic spectators will collide with work commuters at popular transfer stations during the morning rush hour, while small stations closest to venues will be overwhelmed.

Add to the mix, newcomers carrying luggage aboard subway cars and struggling to maneuver off the train and through crowded stations.

Tokyo transport officials characterize train cars at 200% capacity as giving passengers just enough space to read a magazine. This probably represents a normal commuting weekday in Tokyo.

At 250%, they “cannot even move a hand.”

Taguchi’s study predicts 15 stations will experience greater than 200% capacity, with several reaching nearly 400% at their peak.

Since Tokyo last hosted the Summer Olympics in 1964, railways have designated special oshiya, or “pushers,” to pack commuters into rush hour cars— often wearing white gloves. Locals are accustomed to the treatment, but visitors may not be.

Tokyo’s Olympic organizing committee question Taguchi’s dire predictions. They acknowledge the railways will be packed with 800,000 added passengers daily. They also anticipate that Tokyo expressway congestion will double.

Hoping to head off the crowding, the committee wants to launch a smartphone app, boost multilingual signage, and use boats and robot-assisted technology to help fans and commuters get around. As with all Olympics, authorities are testing special highway lanes and altering the city’s transit flow.

Concerns about transportation are nothing new at the Olympics, and crowds are often overestimated and subsequently managed, as was the case in London in 2012. Potential tourists sometimes stay away, knowing it’s a bad time to visit with prices soaring. That happened in 2008 in Beijing and again three years ago in Rio de Janeiro.

“Living in Tokyo we experience this 100%, 150%, 180% crowding every day. We know how to navigate the stations at these times,” said Katsuhisa Saito, the head of transport strategy for Tokyo’s organizers. “The main concern is when foreigners attend these events and use the stations. They might not know how to deal with this.”

Organizers hope to bring the level of congestion in subway cars down to between 150-180%, a fairly pleasant day for Tokyo commuters. Also, perhaps, a lofty goal.

Taguchi and organizers agree on one thing: keeping Japanese workers at home during the Olympics could go a long way toward solving the problems.

Organizers are asking companies in Tokyo to encourage their employees to work from home during the Olympics, which open on July 24, 2020, and close on Aug. 9. They say more than 2,000 companies have agreed to participate.

Tokyo University professor Katsuhiro Nishinari is working with the organizing committee, an expert in what he calls “jam-ology” — the study of crowd behavior.

“We’re used to having one game per day at the stadium, but at the Olympics we have a tight schedule and we have 3-4 games in one day,” he said. “We have to exchange the audience two or three times. That’s where we don’t have experience.”

Another major challenge will be convincing a famously industrious workforce to avoid the commute — or the office altogether — for two weeks next summer.

“We’re explaining to all the companies and the media, asking people not to work during those two weeks,” Nishinari said. “Just enjoy the Olympics.”