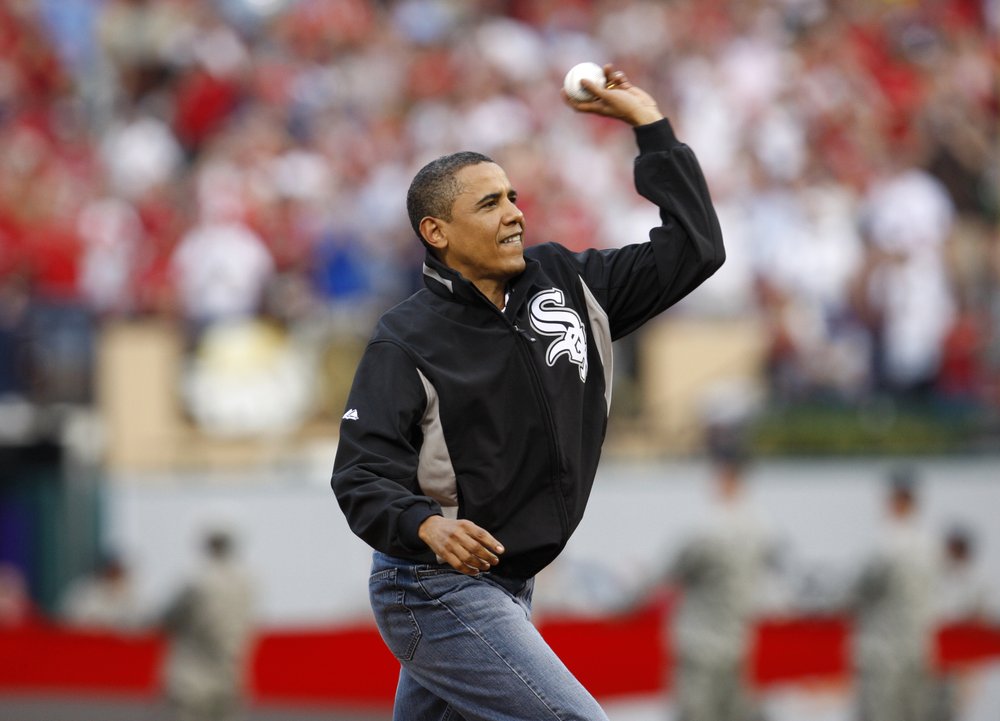

FILE – In this July 14, 2009, file photo, President Barack Obama throws out the ceremonial first pitch during the MLB All-Star baseball game in St. Louis. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh, file)

NEW YORK — President Donald Trump’s plan to attend Game 5 of the World Series on Sunday will continue a rich tradition of intertwining the American presidency with America’s pastime.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s limousine drove onto to the field ahead of the 1933 World Series, the last time the nation’s capital hosted the Fall Classic. Congressional hearings on the stock market collapse were postponed so senators could attend the game.

Harry S. Truman tossed out a first pitch from the stands of a regular season game in August 1945, just days after the end of World War II, giving Americans a sense that normalcy was returning after years of global conflict.

George W. Bush wore a bulletproof vest under his jacket when he threw a perfect strike from the Yankee Stadium mound during the 2001 World Series, not 10 miles from where the World Trade Center was attacked a month earlier.

Trump, who has yet to throw out a ceremonial first pitch since taking office, plans to arrive after the Washington Nationals and Houston Astros are underway and leave before the final out, in hopes of making his visit less disruptive to fans, according to Rob Manfred, baseball’s commissioner.

While it will be Trump’s first time attending a major league game as president, he has deep ties to the sport.

A longtime New York Yankees fan who was spotted regularly at games in the Bronx, he was also a high school player with enough talent that, he has said, he drew the attention of big-league scouts.

Presidential attendance at baseball games has “become an institution and a unifying influence in a nation that is losing both,” said Curt Smith, a former Bush speechwriter and author of “The Presidents and the Pastime.”

“It is part of the job description, irrespective of whether the president is a Republican or a Democrat or a liberal or a conservative. Bush found it a joy, he understood the symbolism of the moment. And he was the rule, not the exception,” Smith said.

Trump mentioned his World Series plan to reporters in the Oval Office on Thursday. But when asked whether he might throw out the first pitch, he said, “I don’t know. They’re going to have to dress me up in a lot of heavy armor,” apparently referring to a bulletproof vest. “I’ll look too heavy. I don’t like that.”

But the Nationals, who decide on ceremonial first pitches, made clear that the president was not asked to take the mound. That honor instead will go to a notable Trump critic, celebrity chef Jose Andres, whose humanitarian work has been widely acclaimed.

Andres, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Spain, has been a longtime critic of the president’s views on immigrants and he halted plans to open a restaurant at the Trump International Hotel in downtown Washington. The Trump Organization then sued Andres, who also denounced the administration for failing to do enough to help the people of Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria in 2017.

There’s some suspense around how Trump might be greeted at the game.

Though the fans at the high-priced event are likely to skew more corporate than at a regular season Nationals contest, Trump is extremely unpopular in the city he now calls home. In the 2016 election, Trump won just 4 percent of the vote from the District of Columbia.

Trump’s White House staff has long tried to shield him from events where he might be loudly booed or heckled, and he rarely ventures out into the heavily Democratic city. (With the exception of his hotel, a Republican-friendly oasis a few blocks from the White House.)

“It’ll be loud for Trump but every president gets booed: both Bushes, Reagan, Nixon. When Americans pay for their ticket, most of them buy into the great American tradition to boo whomever they want,” says Smith. “He should embrace it: So what if the elites boo you? Think of how it plays with your voters elsewhere in the country, thinking ‘There they go again, booing our guy.’ Use it!”

Trump has long been a baseball fan, especially of his hometown Yankees. Before he became president, he would be spotted at games, sometimes along the first-base line with then-Fox News host Bill O’Reilly. Trump was also memorably photographed behind home plate across town in the moments after the final outs of the 2006 NLCS when the New York Mets lost to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Trump played high school baseball at New York Military Academy, where he was a star first baseman. His coach, Col. Ted Dobias, told Rolling Stone in 2015 that Trump “thought he was Mr. America and the world revolved around him.”

“He was good-hit and good-field,” Dobias said. “We had scouts from the Phillies to watch him, but he wanted to go to college and make real money.”

Phillies spokesman Greg Casterioto said Friday that the team’s scouting records do not go back that far and there is no way to verify that claim. But Trump, when honoring the 2018 World Series champion Boston Red Sox at the White House in May, fondly remembered his time playing the sport.

“I played at a slightly different level,” Trump said, “but every spring I loved it. The smell in the air.”

That event also underscored Trump’s tumultuous relationship with professional sports. Several Red Sox stars, including Mookie Betts, and the team’s manager, Alex Cora, declined to attend the White House ceremony. Trump has disinvited other championship teams, including the Golden State Warriors and Philadelphia Eagles, from attending after some of their players criticized him.

Trump is, so far, the only president since William Howard Taft in 1910 not to have thrown a first pitch at a major league game. (The first president known to attend a game was Benjamin Harrison in 1892). Calvin Coolidge, nearly a decade before Roosevelt, was the only other president to attend a World Series game in Washington.

Trump will sit with league officials and likely watch from a luxury box, behind security and away from much of the crowd. That would be very different from some of his predecessors, including John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, who sat by the field for their ceremonial duties.

“In the old days, they would throw from the presidential box,” said baseball historian Fred Frommer, who has written several baseball books, including a pair of histories about Washington baseball. “Players from both teams would line up on the first base line and would fight for it, like a mosh pit. And whoever emerged with it would take it to the president for a signature.”