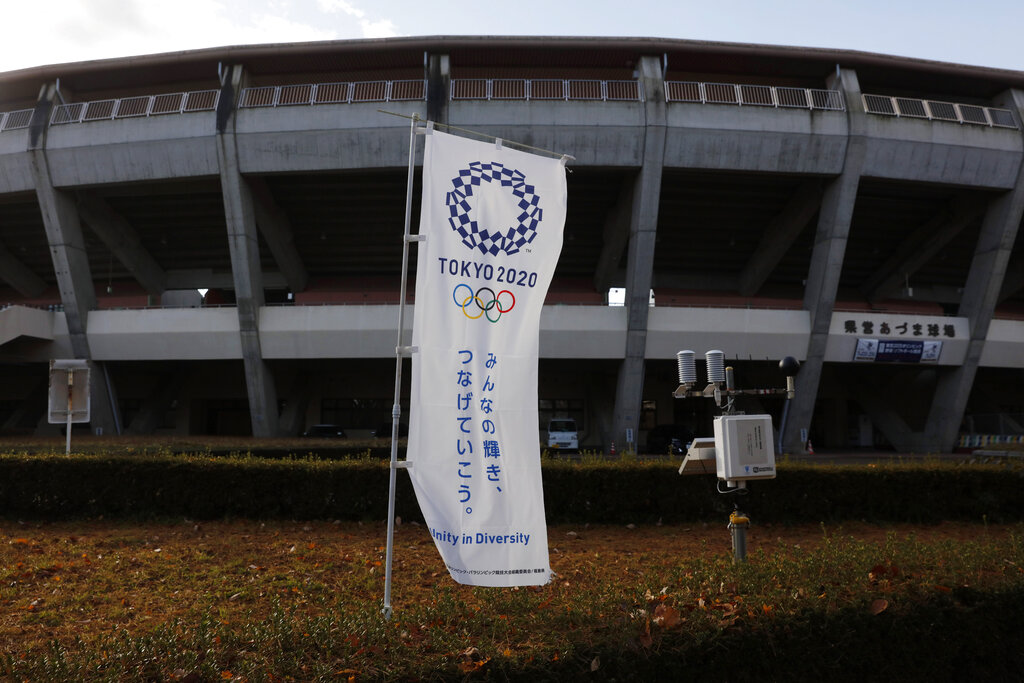

A Tokyo 2020 banner stands in front of the Azumi Baseball Stadium, a venue for baseball and softball at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, Saturday, Nov. 30, 2019, in Fukushima, Fukushima prefecture, Japan. The torch relay for the Tokyo Olympics will kick off in Fukushima, the northern prefecture devastated almost nine years ago by an earthquake, tsunami and the subsequent meltdown of three nuclear reactors. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

FUTABA, Japan — The torch relay for the Tokyo Olympics will kick off in Fukushima, the northern prefecture devastated almost nine years ago by an earthquake, tsunami and the subsequent meltdown of three nuclear reactors.

They’ll also play Olympic baseball and softball next year in one part of Fukushima, allowing Tokyo organizers and the Japanese government to label these games the “Recovery Olympics.” The symbolism recalls the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, which showcased Japan’s reemergence just 19 years after World War II.

But tens of thousands still haven’t recovered in Fukushima, displaced by nuclear radiation and unable to return to deserted places like Futaba.

Time stopped in the town of 7,100 when disaster stuck on March 11, 2011.

Laundry still hangs from the second floor of one house. Vermin gnaw away at once intimate family spaces, exposed through shattered windows and mangled doors. The desolation is deepened by Japanese tidiness with shoes waiting in doorways for absent owners.

“This recovery Olympics is in name only,” Toshihide Yoshida told The Associated Press. He was forced to abandon Futaba and ended up living near Tokyo. “The amount of money spent on the Olympics should have been used for real reconstruction.”

Japan is spending about $25 billion to organize the Olympics. Most is public money, though exactly what are Olympic expenses — and what are not — is always disputed.

The government has spent 34.6 trillion yen ($318 billion) for reconstruction projects for the disaster-hit northern prefectures, and the Fukushima plant decommissioning is expected to cost 8 trillion yen ($73 billion).

The Olympic torch relay will start in March in J-Village, a soccer stadium used as an emergency response hub for Fukushima plant workers. The relay goes to 11 towns hit by the disaster, but bypasses Futaba, a part of Fukushima that Olympic visitors will never see.

“I would like the Olympic torch to pass Futaba to show the rest of the world the reality of our hometown,” Yoshida said. “Futaba is far from recovery.”

The radiation that spewed from the plant at one point displaced more than 160,000 people. Futaba is the only one of 12 radiation-hit towns that remains a virtual no-go zone. Only daytime visits are allowed for decontamination and reconstruction work, or for former residents to check their abandoned homes.

The town has been largely decontaminated and visitors can go almost anywhere without putting on hazmat suits, though they must carry personal dosimeters — measures radiation absorbed by the body — and surgical masks are recommended. The main train station is set to reopen in March, but residents won’t be allowed to return until 2022.

A main-street shopping arcade in Futaba is lined by collapsing store fronts and sits about 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) from the nuclear plant, and 250 kilometers (150 miles) north of Tokyo. One shop missing its front doors advertises Shiseido beauty products with price tags still hanging on merchandise. Gift packages litter the ground.

Futaba Minami Elementary School has been untouched for almost nine years and feels like a mausoleum. No one died in the evacuation. But school bags, textbooks and notebooks sit as they were when nearly 200 children rushed out.

Kids were never allowed to return, and “Friday, March 11,” is still written on classroom blackboards along with due dates for the next homework assignment.

On the first floor of the vacant townhall, a human-size “daruma” good-luck figure stands in dim evening light at a reception area. A piece of paper that fell on the floor says the doors must be closed to protect from radiation.

It warns: “Please don’t go outside.”

The words are underlined in red.

“Let us know if you start feeling unwell,” Muneshige Osumi, a former town spokesman told visitors, apologizing for the musty smell and the presence of rats.

About 20,000 people in Japan’s northern coastal prefectures died in the magnitude-9.0 earthquake and resulting tsunami. Waves that reached 16 meters (50 feet) killed 21 people around Futaba, shredding a seaside pine forest popular for picnics and bracing swims.

A clock is frozen at 3:37 p.m. atop a white beach house that survived.

Nobody perished from the immediate impact of radiation in Fukushima, but more than 40 elderly patients died after they were forced to travel long hours on buses to out-of-town evacuation centers. Their representatives filed criminal complaints and eventually sent former TEPCO — Tokyo Electric Power Company — executives to court. They were acquitted.

When Tokyo was awarded the Olympics in 2013, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe assured International Olympic Committee members that the nuclear disaster was “under control.” However, critics say the government’s approach to recovery has divided and silenced many people in the disaster-hit zones.

Under a development plan, Futaba hopes to have 2,000 people — including former residents and newcomers such as construction workers and researchers — eventually living in a 550-hectare site.

Yoshida is unsure if he’ll return. But he wants to keep ties to Futaba, where his son inherited a filling station on the main highway connecting northern Japan to Tokyo.

Osumi, the town spokesman, said many former residents have found new homes and jobs and the majority say they won’t return. He has his own mixed feelings about going back to his mountainside home in Futaba. The number of residents registered at the town has decreased by more than 1,000 since the accident, indicating they are unlikely to return.

“It was so sad to see the town destroyed and my hometown lost,” he said, holding back tears. He reflected on family life, the autumn leaves, and the comforting hot baths.

“My heart ached when I had to leave this town behind,” he added.

Standing outside the Futaba station, Mayor Shirou Izawa described plans to rebuild a new town. It will be friendly to the elderly, and a place that might become a major hub for research in decommissioning and renewable energy. The hope is that those who come to help in Fukushima’s reconstruction may stay and be part of a new Futaba.

“The word Fukushima has become globally known, but regrettably the situation in Futaba or (neighboring) Okuma is hardly known,” Izawa said, noting Futaba’s recovery won’t be ready by the Olympics.

“But we can still show that a town that was so badly hit has come this far,” he added.

To showcase the recovery, government officials say J-Village — where the torch relays begins — and the Azuma baseball stadium were decontaminated and cleaned. However, problems keeping popping up at J-Village with radiation “hot spots” being reported, raising questions about safety heading into the Olympics.

The radioactive waste from decontamination surrounding the plant, and from across Fukushima, is kept in thousands of storage bags stacked up in temporary areas in Futaba and Okuma.

They are to be sorted — some burned and compacted — and buried at a medium-term storage facility for the next 30 years. For now they fill vast fields that used to be rice paddies or vegetable farms. One large mound sits next to a graveyard, almost brushing the stone monuments.

This year, 4 million tons of those industrial container bags were to be brought into Futaba, and another million tons to Okuma, where part of the Fukushima plant stands.

Yoshida says the medium-term waste storage sites and the uncertainty over whether they will stay in Futaba — or be moved — is discouraging residents and newcomers.

“Who wants to come to live in a place like that? Would senior officials in Kasumigaseki government headquarters go and live there?” he asked, referring to the high-end area in Tokyo that houses many government ministries.

“I don’t think they would,” Yoshida added. “But we have ancestral graves, and we love Futaba, and we don’t want Futaba to be lost. The good old Futaba that we remember will be lost forever, but we’ll cope.”