Ryan Newman Daytona 500 crash shows racing never truly safe

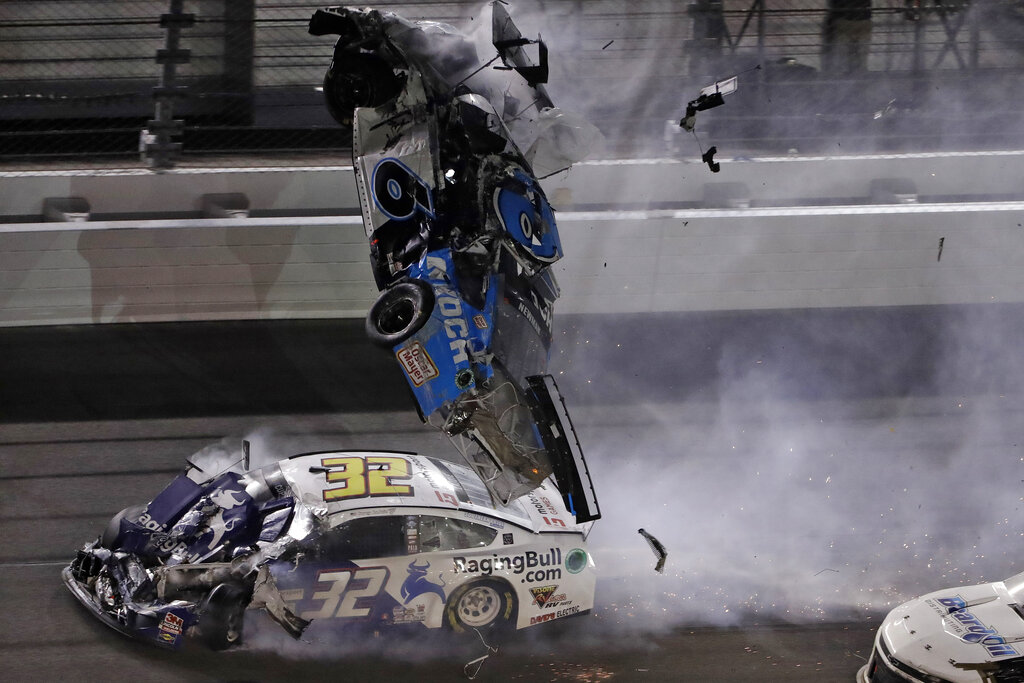

Ryan Newman (6) goes airborne after crashing into Corey LaJoie (32) during the NASCAR Daytona 500 auto race Monday, Feb. 17, 2020, at Daytona International Speedway in Daytona Beach, Fla. Sunday’s running of the race was postponed by rain. (AP Photo/Chris O’Meara)

DAYTONA BEACH, Florida— Dale Earnhardt’s death on the final lap of the Daytona 500 may have saved Ryan Newman’s life.

Earnhardt died 19 years ago Tuesday, the same day Roush Fenway Racing said Newman was awake and talking to doctors and family following his own harrowing accident on the last lap of the biggest race of the year.

Article continues after this advertisementEarnhardt died instantly when he hit the wall at Daytona International Speedway in what is considered the darkest day in NASCAR history. It triggered a chain reaction of safety improvements as the sanctioning body put a massive emphasis on protecting its drivers.

So it was jarring when Newman went airborne on the final lap of Monday night’s rain-rescheduled Daytona 500 — a grim reminder that racing cars at 200 mph inches away from other drivers will never be safe.

Newman had just taken the lead when fellow Ford driver Ryan Blaney received a huge push from Denny Hamlin that put Blaney on Newman’s bumper. At that point, Blaney said his only goal was to push Newman across the finish line so a Ford driver would beat Hamlin in a Toyota. Instead, their bumpers never locked correctly and the shove Blaney gave Newman caused him to turn right and hit a wall. His car flipped, went airborne, and was drilled again in the door by another driver. That second hit sent the car further into the air before it finally landed on its hood and slid toward the finish line at Daytona International Speedway.

Article continues after this advertisementHis spotter pleaded with Newman on the in-car radio “Talk to me when you can, buddy,” but no words came from the driver.

An industry so accustomed over the last two decades to seeing drivers climb from crumpled cars with hardly a scratch held its breath as it took nearly 20 minutes for the 42-year-old to be removed from the car. It was another two hours before NASCAR said Newman was in serious condition at a hospital with non-life threatening injuries.

Roush Fenway Racing said Tuesday that Newman “is awake and speaking with family and doctors. Ryan and his family have expressed their appreciation for the concern and heartfelt messages from across the country. They are grateful for the unwavering support of the NASCAR community and beyond.”

No information was given on specific injuries.

This was a scare NASCAR has dodged for 19 years. Carl Edwards sailed into a fence at Talladega in 2009, climbed from the burning wreckage and then jogged across the finish line to complete the race. Kyle Larson in a 2009 Xfinity Series race flew into the Daytona fencing and walked away unscathed even though the front half of his car had been completely torn away.

Kyle Busch crashed into a concrete wall at Daytona the day before the 500 in 2015. He broke both his legs and still was able to get himself out of the car. Five months later, Austin Dillon ripped out a section of Daytona fencing, landed upside down in a destroyed race car, and after he was pulled to safety by team members, he flapped both hands in the air for the crowd in a tribute to the signature celebration of the late bull-rider Lane Frost.

Perhaps it has created a false sense of security in today’s cars because so many drivers have walked away from so many accidents.

“The number one thing that NASCAR always does is put safety before competition, you’ve got to have a car that’s safe,” said Hamlin, who went on to win his third Daytona 500 in the last five years. “You’ve got to have all your equipment that’s safe, and the sport has been very fortunate to not have anything freak or weird happen for many, many years. But a lot of that is because of the development and the constant strive to make things better and safer.

“I thank my lucky stars every day that I came in the sport when I did.”

Just five years before Hamlin arrived on the scene, Earnhardt was the fourth driver to die of a basilar skull fracture in an eight-month span. Adam Petty was killed in a 2000 crash at New Hampshire, a mere hundred or so yards from where Kenny Irwin had a fatal impact two months later. Tony Roper was killed in October in a crash at Texas.

But Earnhardt’s death shook the sport to its core. The seven-time champion was the toughest man anyone knew and no crash was going to claim The Intimidator.

Only Earnhardt was an old-school racer still using his preferred routines. He wore customized open-faced helmets, sat low in his seat in a position that almost looked as if he was reclined, and, allegedly adjusted his seatbelts from the recommended installation settings to a position that suited his comfort level.

NASCAR acted quickly and speculation over Earnhardt’s seat belts led teams to move from traditional five to six-point safety harnesses.

NASCAR also encouraged its drivers to begin wearing a head-and-neck restraint system, and by August of that year 41 of the 43 drivers in the field at Michigan were using them. The device was not made mandatory until 2001, after Blaise Alexander was killed in an ARCA race at Charlotte. Tony Stewart resisted the device because he argued it made him feel claustrophobic in the car, but NASCAR refused to let him on track until he put on the restraint.

The HANS device is now mandatory in nearly every professional racing series, from Formula One to IndyCar and even dirt racing.

Indianapolis Motor Speedway had already been developing softer walls, and NASCAR finally got on board with the process after Earnhardt’s death. Although the SAFER Barriers are credited to IndyCar’s development, NASCAR contributed to the research costs and began installation in the corners at its tracks. The softer walls slowly evolved to more areas of tracks following hard hits by Jeff Gordon, Elliott Sadler, and other top stars. After Busch broke his legs at Daytona by hitting a part of the wall not protected with energy-absorbing foam, NASCAR increased installation of the safety measure across the entire series.

NASCAR also began requiring containment seats – more of an amusement park ride-style setup than a traditional car seat. Development was done to improve helmets, restraint systems and cockpit safety.

Then came in 2006 the Car of Tomorrow, built specifically as the safest stock car ever run in NASCAR. The car had energy-absorbing foam in the doors and tougher crush zones. The car was a tank, designed to keep drivers alive.

The car was replaced by the “Gen 6” in 2014 with a new chassis aesthetic changes, and it will be replaced next year by the “Next-Gen” car designed to cut costs, improve competition and give manufacturers wider access to personalized identification. It will be as safe as NASCAR can build it, but no innovation can guarantee the safety of any driver.

“We know the risks,” Juan Pablo Montoya told The Associated Press on Tuesday. Montoya in 2012 slammed into a jet dryer at Daytona in a collision that caused an immediate fireball and had the tough Colombian gingerly walking away from the scene.

But Montoya did walk away, as did Corey LaJoie on Monday night after hitting Newman’s flying car directly on the driver’s side. LaJoie’s car caught fire but he was able to get out onto the track, where he dropped to his knees and waited for medical personnel.

That’s what everyone waited for with Newman, too, but the length of time it was taking the safety crew to attend to his overturned car and his silence on the radio was ominous. Hamlin’s team was widely criticized for celebrating the victory, but team owner Joe Gibbs insisted they had no idea Newman’s situation was serious.

“If you think about all the wrecks that we’ve had over the last, I don’t know, how many number of years, and some of them looked real serious, we’ve been so fortunate,” Gibbs said. “Participating in sports and being in things where there’s some risk … in a way, that’s what (drivers) get excited about. We know what can happen. You just don’t dream that it would happen.”

Newman appears to be improving, a welcome relief the day after NASCAR’s showcase event ended in horror. Newman was lucky; Justin Wilson was not in a fatal 2015 IndyCar fluke when a broken part from the leader bounced on the track and hit him in the head nearly 18 positions back in traffic.

Newman’s accident is part of the thrill that draws fans to the sport, and an adrenaline rush that fuels the drivers. That he survived is because of nonstop work on safety for nearly two decades. That work will never end.