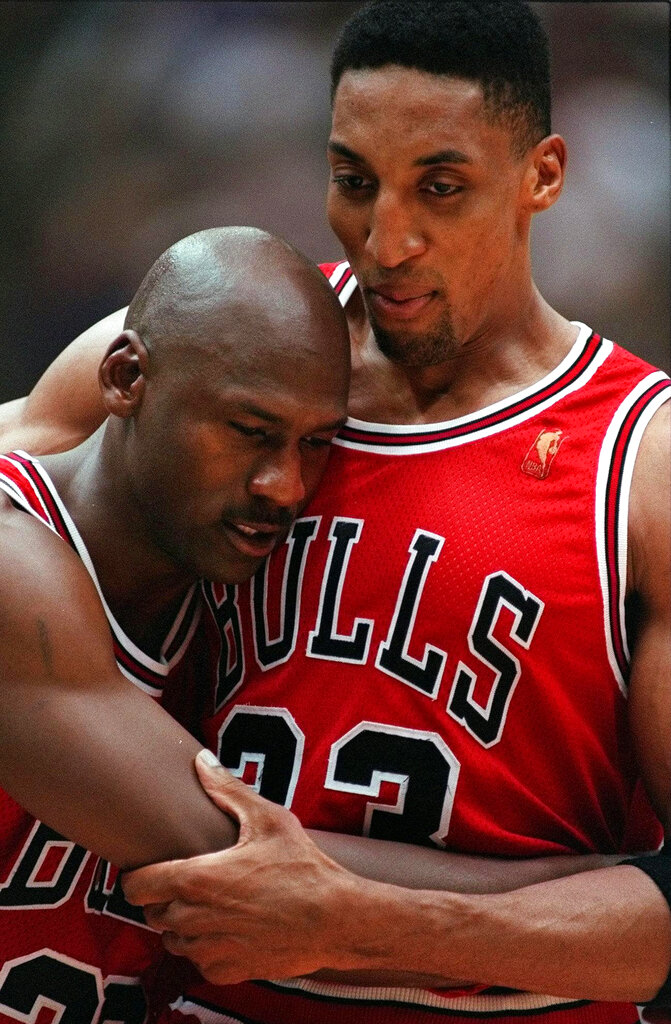

FILE – In this June 11, 1997 file photo, Chicago Bulls Scottie Pippen, right, embraces an exhausted Michael Jordan following their win in Game 5 of the NBA Finals against the Utah Jazz, in Salt Lake City. The flu-like illness Jordan fought through to lead the Bulls to a crucial victory in the 1997 NBA Finals created instant fodder for the virtue of perseverance. Pushing past boundaries, overcoming obstacles and adversity — that is part of the ethos of major competitive sports. That is how elite athletes become wired to win. (AP Photo/Jack Smith, File)

MINNEAPOLIS — The flu-like illness Michael Jordan fought through to lead the Chicago Bulls to a crucial victory in the 1997 NBA Finals created instant fodder for the virtue of perseverance.

Pushing past boundaries, overcoming obstacles and adversity — that is part of the ethos of major competitive sports. That is how elite athletes become wired to win.

It is also in direct conflict with the medical wisdom currently steering society in a bid to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Think about Jordan’s “Flu Game” through the lens of the pandemic and social distancing. It’s jarring.

Seasons have been on pause for weeks with no end in sight. So, too, has the competitive drive of tens of thousands of the world’s best athletes, the bottle corked by simple, sobering orders: Back off. Stay home.

“This flew in the face of what they had been taught and socialized to do, which is, ‘Let’s play,’” said John Tauer, the men’s basketball coach and psychology professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

The safety of the living room replaced the comfort of the arena.

“You really don’t know what the next day holds,” Buffalo Sabres star Jack Eichel said. ”Every morning you wake up, you don’t have to go to the rink, you don’t have to perform. … You’re just trying to stay busy and keep your mind in a good, healthy place.”

Eichel has spent some of his quarantine time reading “The Mindful Athlete,” a book by sports psychologist George Mumford, who worked with the Bulls and taught Jordan the art of meditation.

More than two decades later, the brain plays a much bigger role in the way teams teach and guide their performers. Maintaining mental fitness during the pause could be as critical to success as remaining in peak physical condition simply because athletes are facing anxiety in unprecedented ways.

“This may not be a crisis for many of us yet, but it’s still a big enough shift from our daily lives where it causes us to reflect and begin to say, ‘OK, when you pull something away from me that I identify with, how is this working for me? Is this going the way I want it to?’” said Justin Anderson, team psychologist for the Minnesota Timberwolves.

In an occupation built on physical performance, athletes have a short career window, and opportunities to excel are few. For all the financial cushion many have, the identity loss during the shutdown has been severe. Their most elemental function as an employee has disappeared.

In the NFL, a letter from the league and the players’ union sent to players this month included advice on how to deal with the angst, addressing loneliness, stress and other subjects. The global union for soccer players surveyed members and found increased levels of anxiety and depression.

“It’s a really strange environment, especially for athletes when they are used to being on the field, used to being in the gym, used to working out every day,” said Carlos Bocanegra, Atlanta United’s technical director.

College and high school athletes were hit hard, their careers framed by eligibility limits. Last month, when the NCAA shut down all activity, coaches scrambled to keep tabs on their players and keep spirits up.

Tauer’s team, ranked fourth in Division III, was supposed to play rival St. John’s in the national tournament until it was canceled. In his season-ending speech, he encouraged his players to apply their unique experience of being on a team toward the new reality.

“Let’s do what a great teammate does, and that means think about the greater good as opposed to what my immediate wants might be right now,” Tauer said.

The Timberwolves made player wellness one of their top priorities when Gersson Rosas took over a year ago as president of basketball operations. He envisioned an innovative, holistic approach to player development to support the pursuit of a championship.

When the pandemic prompted the NBA to suspend the season, the Timberwolves were mired at the bottom of the Western Conference standings. Off the court, however, they were prepared to help keep the team as intact as possible while forced to sequester.

“Long before this happened, we valued certain things that in a crisis become even more apparent and important,” said Robby Sikka, the team’s vice president for basketball performance and technology. Sikka cited valuing the players’ health and nutrition, being player-centric and family oriented from the beginning.

The job created for Sikka — to integrate medical, technological and analytical knowledge and resources for improving wellness off the court and performance on it — has been vital. The week before the league shut down, he warned players, “This will be your 9/11.”

Since then, he has helped coordinate player efforts to not only stay in shape with the practice facility closed but make sure mental health needs are being met. He sees it as setting up lifelong coping skills. Anderson has paid particular attention to anxiety management.

“It’s not something you either have or you don’t have. It’s something you develop, much like their shooting percentage or any other skill that they’re working on,” Anderson said.

Just because they’re some of the greatest athletes in the world doesn’t mean they don’t have flaws.

“At the end of the day, they have families, they have needs, they have challenges, that, if we choose to ignore them, we’re choosing to ignore them as individuals,” Rosas said. “That’s an area where we don’t want to fail.”