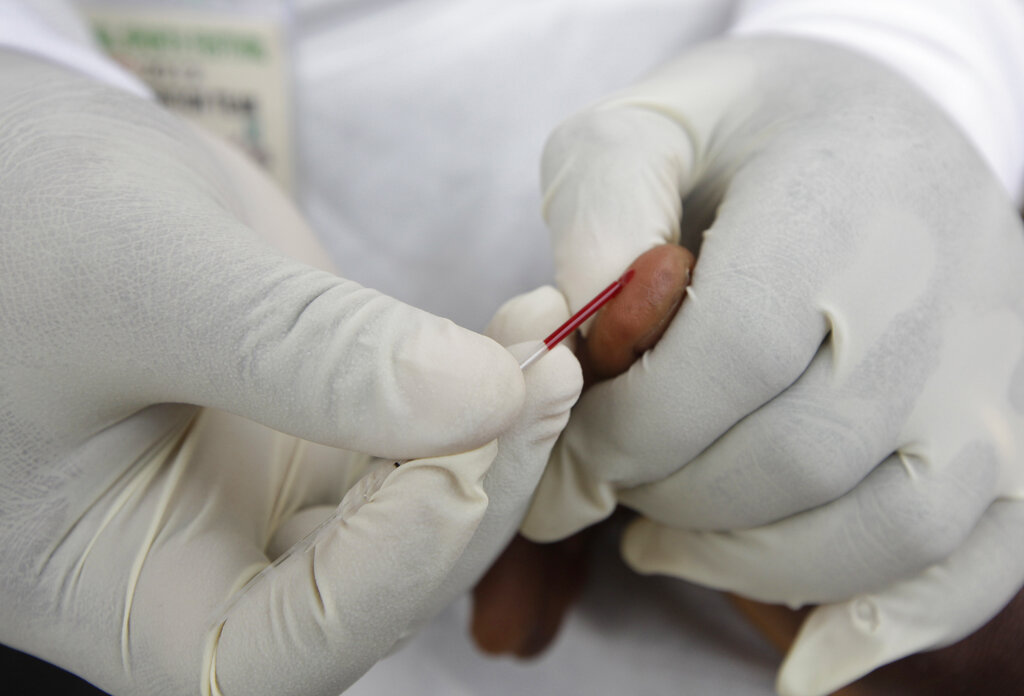

FILE – In this file photo dated Saturday, Dec. 1, 2012, a doctor takes a blood test from an athletes during the 18th National Sports Festival in Lagos, Nigeria. The World Anti-Doping Agency is looking to artificial intelligence as a new way to detect athletes who cheat, it is revealed Tuesday May 26, 2020, funding four projects in Canada and Germany, looking at whether AI could spot signs of drug use. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba, FILE)

DÜSSELDORF, Germany— With sports around the world shut down by the coronavirus pandemic, the World Anti-Doping Agency is looking to artificial intelligence as a new way to detect athletes who cheat.

WADA is funding four projects in Canada and Germany, looking at whether AI could spot signs of drug use which might elude even experienced human investigators. It’s also grappling with the ethical issues around the technology.

Athletes won’t be suspended solely on the word of a machine. Instead, AI is a tool to flag up suspect athletes and make sure they get tested.

“When you are working for an anti-doping organization and you want to target some athletes, you look at their competition calendar and you look at their whereabouts, you look at the previous results and so forth,” WADA senior executive director Olivier Rabin told The Associated Press in a recent interview. “But there is (only) so much a brain can process in terms of information.”

The pandemic has shut down anti-doping testing in many countries, but it’s pushed AI work to the fore, since much research can be done remotely.

Analyzing an athlete’s blood or urine sample is about more than just finding a performance-enhancing substance. Tests also track numerous biomarkers like an athlete’s red blood cell count or testosterone levels.

That kind of information is already used by anti-doping bodies in the “biological passport” program to detect the effects of using something like the blood-booster EPO, the substance used by Lance Armstrong.

WADA hopes AI can help improve that system by tracking patterns between those markers and cross-referencing them with other information. One of WADA’s projects aims to make EPO detection more precise and another hopes to do the same for steroids.

Machine learning systems can be taught by showing them confirmed “dirty” and “clean” profiles to detect similarities which may not be visible on the surface.

There’s also what Rabin calls a “global” project in Montreal which could predict the risk of doping by evaluating data from a wider range of sources, possibly including the information athletes are required to file about their whereabouts. Athletes’ personal data and even the names of the cities where they live and train will be anonymized because of privacy concerns.

“It’s been fairly complex discussions … to try to find a balance between, you know, again, protecting data, protecting individuals and making sure that you can still reveal the potential of AI, if there is any,” Rabin said.

Athletes’ results in competition aren’t yet part of the mix.

“Maybe in the future but not for now,” Rabin said.

AI can be an expensive area of science, with specialists in high demand. Three projects in Canada cost WADA about $425,000 over two years, with matching funding from the province of Quebec’s research funds, and there’s another $60,000 for the EPO project in Germany, WADA said.