For three boxers, it’s been a long journey to Tokyo Olympics

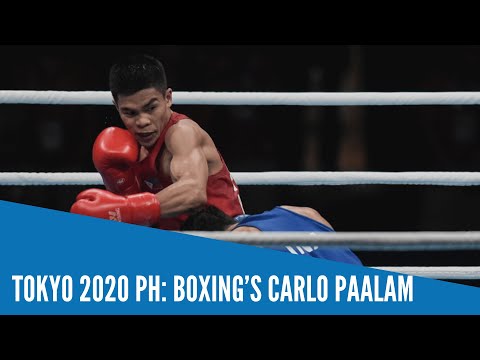

DECEMBER 9, 2019: Philippines’ Carlo Paalam celebrates after defeating Indonesia’s Langu Kornelis Kangu to claim the gold medal during the 30th South East Asian Games 2019 Men’s Light Flyweight Final (46-49 kg). INQUIRER PHOTO/ Sherwin Vardeleon

A bottle of Coke.

That’s the first thing Carlo Paalam ever fought for in his life. His neighbor called him one day to spar with his son and Paalam refused.

“I was scared sir,” he said in Filipino. “The kid’s dad was a boxer and he was really good.”

That was when the bottle of Coke was thrown in as a prize. Even in a sport where some boxer named Manny Pacquiao—last we heard the guy is a billionaire—once fought for P150, a bottle of Coke seems top be a measly prize to bait a young kid into getting into a scrap.

Not for Paalam, though.

“I was just a nine-year-old kid then. Once there was a bottle of coke as prize, I put on the gloves,” Paalam said.

It was a treat, the Cagayan de Oro native said, for someone who would push wooden carts and collect plastic scraps and empty bottles to help his family earn a living.

From the background on the multiscreen Zoom call, Nesthy Petecio and Irish Magno teased their teammate: “He’s going to cry, sir,” they said, laughing.

It could be that they’ve seen Paalam tear up before. But it could also have been because they know exactly what he had gone through.

Until Petecio became a decorated national boxer, she and her family had never tasted a sumptuous Christmas dinner. They just couldn’t save up for it.

That changed in 2005, when Petecio, who dabbled in a lot of sports before, watched a women’s boxing match in the Southeast Asian Games and saw a Filipino stand on the top podium while the national anthem was being played.

“I told my father I wanted to be that person,” she said.

Magno, on the other hand, was faced with a choice: Loiter around as her family languished in poverty or box her way to a regular income.

“It’s either I help my family or be a burden to them,” she said.

She didn’t really have to think hard.

For Paalam, the turning point came when he won that bottle of Coke. His opponent’s dad saw the promise he had and took the young Carlo under his wing. He began participating in weekly boxing tournaments, this time for prize money worth P120.

“That was big,” he said. “I could spend a whole day collecting plastic scraps and selling them and I wouldn’t earn as much as I would if I boxed for a few minutes.”

Besides, P120 was a big leap from a bottle of Coke.

From whatever hardships they crawled out of, Paalam, Petecio and Magno have made it to Tokyo. Together with pro Eumir Felix Marcial, the boxers are one of the vaunted teams here and one of the brightest hopes for a gold medal. And the prize awaiting them for victory in the Olympics is quite a leap from P120. And definitely much more than a bottle of Coke.

A gold medal winner in the Games could end up taking home P50 million. People who have done also much more in their lifetime than pushing wooden carts and collecting scraps will not even get to within seeing distance of that amount.

“This is no longer just an interbarangay tournament,” Magno said.

“I’m really excited to fight,” Paalam said. “We’re really ready to fight and give our best for the country.”

If you doubt the sincerity of his words, remember that a little more than a decade ago, a nine-year-old kid put on gloves for the first time to fight for much, much less.