Hidilyn Diaz said she won’t be retiring anytime soon, and it would be devastating if she can’t defend her gold in 2024. —AFP

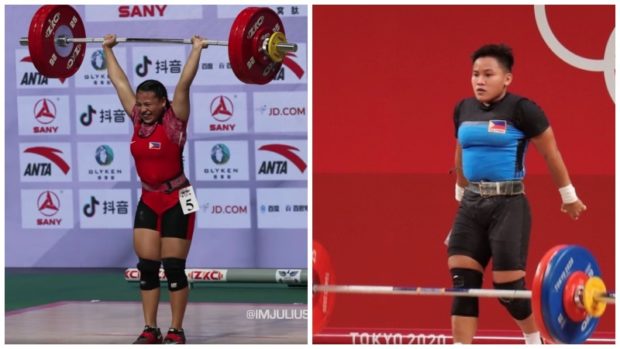

Elreen Ann Ando finished seventh in the women’s weightlifting 64-kilogram division in her Olympic debut at Tokyo International Forum here.

In a sport that delivered the country’s first Olympic gold medal in history, seventh place may seem like an asterisk, a feat that would have a hard time finding its place in a Hall-of-Fame museum.

But Ando was never meant to compete in Tokyo anyway. She was a last-minute callup to this year’s delayed Summer Games and she made the most of that stint.

“I’m very happy [to have competed in Tokyo],” she said via a phone call from her quarantine room in a hotel in Manila, after flying back to the Philippines the day after her competition. “I improved the national record [in my division] and got to experience the Olympics. I’m very inspired.”

Before she got the wild card berth, however, she was already busy training—“every day, except Sundays,” she said—for the original goal mapped out for her by her national federation: Paris 2024.

Trailblazer

Meanwhile, more that 3,000 kilometers from Tokyo, in Bohol, Philippines, Issai Danao, a weightlifting trailblazer who was among the first Filipino women to compete in the sport in an international competition, said she is excited about the buzz surrounding weightlifting in the grassroots.

The buzz, fueled by the historic triumph of Hidilyn Diaz in the 55-kg women’s division here, may just supercharge weightlifting’s growth locally, she said. Diaz locked up a spot for herself among the country’s sporting legends when she ended the Philippines’ near-century wait for an Olympic gold.

“Ever since the gold medal, the grassroots has come alive,” Danao said. “The challenge is how to sustain it and make sure the kids don’t lose interest. It will be up to the coach or trainer to keep encouraging the young lifters.”

Danao herself trains kids interested in weightlifting, including 8-year-old Veronica Sarno, the younger sister of Asian 71-kg champion Vanessa Sarno.

Sarno, 17, is one of five lifters the Samahang Weightlifting ng Pilipinas (SWP) is sharpening for one goal: Paris 2024.

“With or without the participation of our heroine, Hidilyn Diaz, we can still get medals, but we’re still not sure what color,” said SWP president Monico Puentevella.

That’s why the former member of the House of Representatives is gearing up for a crucial battle that is going to happen at the end of the month, one that will determine the fate of the sport when it comes to the one event everybody in the Philippine weightlifting community is looking forward to: Paris 2024.

Crucial Doha meet

The International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) will convene its officials on Aug. 28 and 29 in Doha, Qatar, as it rushes to comply with an order from the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to revamp its constitution. The IWF has already attempted to do so last June 30, but a “rivalry over amendments and ideas” between the current administration of the federation and a group of European officials stalled the amendments, Puentevella said.

The Doha conclave is now faced with a serious threat. In a strongly-worded letter, Puentevella revealed, the IOC issued an order to the IWF: Amend the constitution or risk weightlifting getting scrubbed from Paris 2024 and beyond.

Central among the issues the IOC wants addressed are corruption, doping and favoritism. Take the doping issue for instance. Several countries, allegedly using their strong ties with the past IWF administration, are being accused of repeatedly circling around doping tests and protocols without getting punished for it.

“The IOC is getting tired of the doping allegations,” Puentevella said. “The IOC wants to apply sanctions that if you can’t discipline yourself, you are in danger with your membership with the IOC.”

Not only does the IOC want amendments to the IWF’s doping rules, it is very specific about the changes it wants shoehorned into the federations by-laws. According to Puentevella, for example, the IOC wants the IWF regulated by the International Testing Agency, an organization that manages anti-doping programs and is based in Luasanne, Switzerland.

That is apart from the regulation and testing handled by the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada), Puentevella said.

“The Philippines is already complying with that,” the weightlifting chief said. “But the IOC wants it in the constitution.”

Avoiding disaster

If the IWF fails anew to vote in the IOC amendments, it would mean disaster for the SWP, which is starting to gain momentum in the grassroots.

“The victory of Hidilyn Diaz would move many children to take up weightlifting,” Puentevella said. “This is the salvo that we need so that weightlifting will be a chosen sport for Filipino kids.”

In Bohol, at least, it is a fast-track path to the national team.

“It’s difficult for kids to get into national teams of other sports,” Danao, a member of the Southeast Asian Games national team in 1991, said. “It’s not easy at all.”

And for many in weightlifting, the sport is the new boxing—a fire exit out of largely impoverished lives.

Ando, for instance, uses her allowance as a national athlete to help pay bills at home and purchase maintenance medicine for her father, who is suffering from the effects of a stroke.

“Because of weightlifting, I was able to finish my studies and help with household expenses,” Ando, who hails from Cebu, said.

Sarno, who made waves after ruling the junior and senior levels of her division in the Asian level, used to train hungry, relying on doleouts from her coaches so she could put food on the family table.

“There was a time when I almost blacked out because I hadn’t eaten yet. They (coaches) gave me money so I could buy rice for my family. They gave me other food, too. My mom was so happy when I got home from training because we had food to eat,” Sarno said in a previous interview.

And she looks to weightlifting to give her more.

“I want my family to have our own house,” she said, adding that living in the oft-ignored fringes of society has often made them the subject of nasty talk of neighbors.

Sarno recently became eligible for a P500,000 bonus from the government for her recent Asian crown.

But for most of these weightlifters, no other tournament offers a richer bounty than the Olympics. Diaz, for example, is expected to pool more than P50 million in bonuses for her gold. Experts say she will pull in even more income through future endorsements.

Apart from bringing glory to flag and country, the chance to haul their family out of the socioeconomic cesspool is a powerful motivation for Ando, Sarno and the other lifters being eyed to compete—and contend—in Paris: Kristen Macrohon, Rosiegie Ramos and John Fabuar.

“It is disastrous for the Philippines if the IOC will think about abolishing weightlifting from the Olympics,” Puentevella said.

“It’s sad to hear [about the IWF’s problems],” Ando said. “We have this opportunity waiting for us and then we hear something like that.”

“It would be a pity for the kids [if weightlifting gets scrapped from the Olympics] because they have ambitions,” Danao added. “Maybe the IOC should just punish, suspend or band the countries that repeatedly break the rules.”

But the ground rules are clear.

“If we do not comply,” Puentevella said, “We may have problems with the IOC.”

Puentevella said he is confident there is a big enough alliance of IWF officials to pass the amendments. “I will fight for that. We will fight and I’m confident we can pull it off.”

His optimism is boosted by the fact that Tamas Ajan, the former IWF chief who in an independent report was fingered as the one accountable for the bribery and doping problems that plagued the federation, has little influence left in the IWF. Ajan resigned from the federation last year while investigation into the IWF was ramped up, Puentevella said.

In the meantime, Ando said that once she clears quarantine protocols, it will be back to training for her and she will continue hoping that the sport’s leadership will do what’s right for the athletes.

“I won’t think about it too much,” she said. Her mind, after all, is set on one thing: Paris 2024.