Hidilyn’s gold, boxers’ varying colors of medals highlight fantastic 2021 for PH sports

Hidilyn Diaz defied the odds and came up with a golden lift in Tokyo where former scavenger Carlo Paalam( bottom photo) won silver in boxing to complete a rags-to-riches story.

The Japanese have a term for it—that which Hidilyn Diaz found in her journey to the Tokyo Olympics.

The word defines that inner intersection where one’s passion, mission, profession and vocation collide, often creating a beautiful explosion of triumph.

It’s called “ikigai,” one’s reason for being.

“This proves we can do it,” Diaz told journalists at Tokyo International Forum minutes after winning the country’s first Olympic gold medal in history by bouncing off Chinese weightlifting record holder Liao Qiuyun in their 55-kilogram showdown. “They said this was impossible. I thought this was impossible. But the Filipino can do it. We just have to believe.”

How easy it could have been for Diaz to have been spiteful and vindictive; to dismiss everyone else who had doubted her—“people said I was over the hill,” she said—and those who cast her in a bad light for seeking help to fund her dream.

And how easy it would have been for the country to forgive her if she went down that path.

Getting back up

But then, that would have meant straying from her ikigai.

The journey to discovering her inner purpose was one she took from the lowest point of her career. In 2012, she failed to complete her lift and crashed out of the London Olympics, a did-not-finish stint that scattered scarring souvenirs online: unflattering photos featuring a fallen Diaz beside a barbell—a symbol of a crushed dream.

Sports officials felt her time was over.

But she came home and restructured that dream, picking herself up piece by piece until she assembled her purpose. Diaz found her vocation, her calling, in a nondescript gym in Zamboanga, where a handful of young children were trying out her sport.

“I wanted to be an inspiration for them,” she told the Inquirer in 2018.

By then, Diaz had exorcised demons of her 2012 flop. She had won a silver medal in the Rio de Janeiro Olympics just two years prior and was celebrating a gold medal in the Asian Games. “I was a nobody and now, people are calling me a sports hero. Who knows? Maybe some unknown kid will be inspired by my accomplishments and become a hero too.”

So she renewed her determination to perfect her profession, slowly constructing a team of trusted individuals to shape her, prod her and keep her singularly focused.

Long wait ends

“I went through a lot, but having Team HD with me made things easier,” Diaz said of a close-knit group that featured coach Gao Kaiwen, strength and conditioning mentor Julius Naranjo, nutritionist Jeaneth Aro and sports psychologist Dr. Karen Trinidad.

Her mission? Pursuing a dream to inspire a nation to crush its lack of self-belief, to replenish a politics-weary population’s faith in itself. Her passion? That gold medal, one that had eluded the country in all its 97 years of participation in the world’s grandest sporting stage.

On the night of June 26 last year, her rebuilt purpose, steeled by months of arduous mental and physical preparations, defied expectations and the challenge of a previously peerless Chinese lifter. She inked two Olympic records in her weight division and ended a country’s quest for a gold medal in the Summer Games.

It was a beautiful moment that redefined the way we look at Olympic victories. For years, Filipino athletes were labeled triumphant merely by showing up. To shield them from the harsh realities of their shortcomings, people looked to moral victories as some sort of a balm.

And then it poured

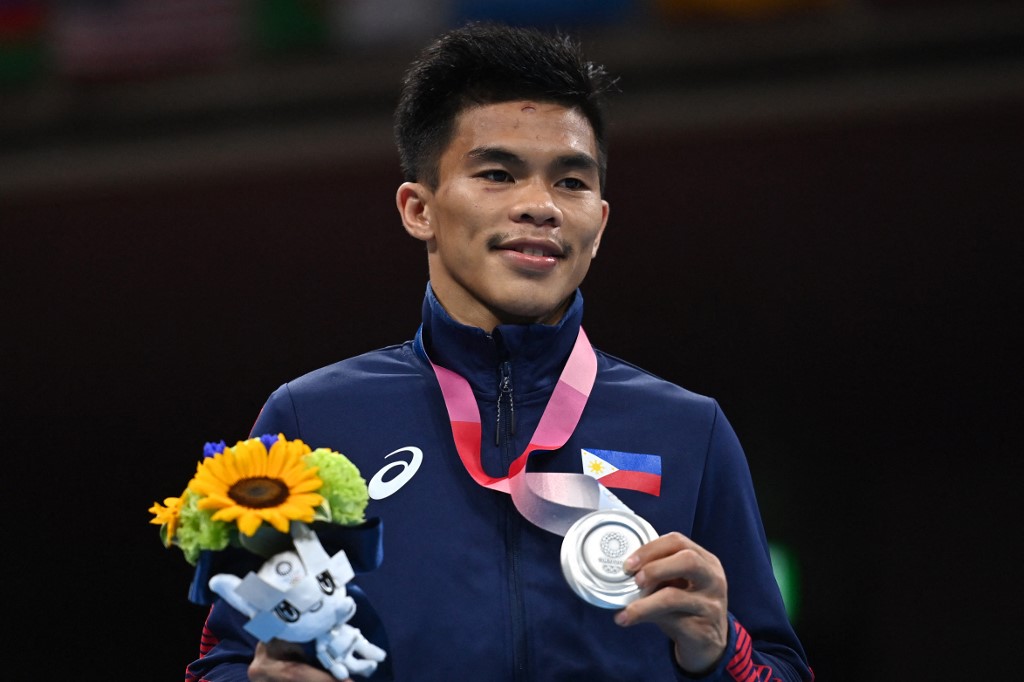

The Philippines’ Carlo Paalam celebrates his silver medal during the medal ceremony for the men’s fly (48-52kg) boxing final bout during the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games at the Kokugikan Arena in Tokyo on August 7, 2021. (Photo by Luis ROBAYO / POOL / AFP)

Diaz reset that bar.

The country’s boxing team followed suit, bringing home two silvers and a bronze medal. Nesthy Petecio and Carlo Paalam forced their opponents to perform beyond their best by producing the fight of their lives. Their silvers awoke a hunger for gold, one both vowed to sate in Paris in 2024. Eumir Marcial’s bronze did the same for the power-punching pro.

And in one fell swoop, the sport that had shouldered a bulk of the country’s Olympic hopes, and some of the most painful defeats of Filipino athletes in the Games, produced a fantastic stint.

Philippine Olympic Committee president Abraham “Bambol” Tolentino called 2021 the country’s golden year in sports.

But already, he has stopped looking at the year as one where a gold hunt ended. It is now the year where Olympic greatness began.

“Yes, the Filipino athlete can win in the Olympics. Yes, we have the capability and we will build on that success,” he said.

The Philippines, indeed, has a lot to look forward to in Paris.

Tolentino is constantly wooing Diaz to defend her gold. Petecio and Paalam know what it takes to win a gold medal match. In Paalam’s case, it took getting knocked down in the first round to deny him a gold—had he managed to stay on his feet, the scores showed, he would have emerged victorious.

Other hopefuls

The Philippines’ gold medalist Carlos Edriel Yulo poses during the medal ceremony for vault event at the men’s apparatus finals during the Artistic Gymnastics World Championships at the Kitakyushu City Gymnasium in Kitakyushu, Fukuoka prefecture on October 24, 2021. (Photo by Charly TRIBALLEAU / AFP)

EJ Obiena, should he find a resolution in the ongoing rift with his national federation, is a medal favorite in pole vault. Carlos Yulo, a gold favorite in Tokyo, rebounded from his failure there to become world champion in yet another gymnastics discipline, giving him two shots at glory in Paris.

Yuka Saso, the golfing sensation who finished strongly in Tokyo after being bogged down by a slow start, may have opted for Japanese citizenship, but the National Golf Association of the Philippines swears it has a concrete program in place to develop her heir.

And the private sector, now handed a blueprint for sporting success, looks more open to fund champions at the start of their journey instead of merely rewarding them for a job well done.

And there are many champions waiting to be discovered.

Diaz left them a message: “You can do this. Fight for the country. Don’t doubt [yourselves]. Believe that you have the strength, you have the power. Be proud to be Pinoy.”And if that leaves them falling short, they can always seek what Diaz found on her way to Tokyo and the gold medal. A sense of purpose. Ikigai.