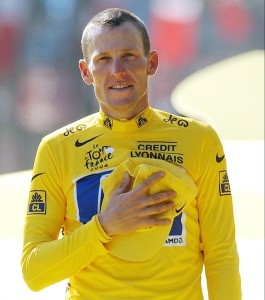

In this July 25, 2004 file photo, Lance Armstrong holds his hand on his chest as he listens to national anthems after winning his sixth straight Tour de France race, in Paris The superstar cyclist, whose stirring victories after his comeback from cancer helped him transcend sports, chose not to pursue arbitration in the drug case brought against him by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency. That was his last option in his bitter fight with USADA and his decision set the stage for the titles to be stripped and his name to be all but wiped from the record books of the sport he once ruled. (AP Photo/Christophe Ena, File)

SAINT-SEBASTIEN-D’AIGREFEUILLE, France — On the hot road to this village in the deepest south of France, we passed the forbidding, barren mountain where Lance Armstrong, the cyclist, took a giant step toward becoming Lance Armstrong, the sporting myth.

It was 12 years ago this summer. Riding hard, Armstrong fiddled with the collar of his bright yellow Tour de France leader’s jersey and tugged its back, getting comfortable in the saddle for one of his trademark attacks.

Then, a few minutes later, he was off, literally like a rocket, leaving rivals for dead and making the towering Mont Ventoux look like little more than a speed bump.

The physical strength he showed that July 13 at the 2000 Tour was mind-boggling. And there were so many other equally mind-boggling moments in the other six Tours he won.

I was there for some of them. The power of Armstrong on the bike, the mix of steely charm and cold, single-minded determination, was like nothing I’d ever seen — both then and since.

Which is why it’s even more mind-boggling to think that none of this really happened. Gone. Expunged. Erased by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency and its finding that the bulk of his career was built on lies and banned performance-enhancing drugs.

The utter destruction of the Lance Armstrong myth, the man seemingly so tough that he not only beat cancer but won the world’s toughest bike race a record seven times, is going to take quite some time to digest.

Other commentators will talk about how this will affect the cancer survivors Armstrong inspired and the foundation he set up to fight the disease. And only the most cynical will say that side of Armstrong should crumble along with his status as a sporting icon.

They will examine how the fall of the only rider who held a candle to Eddy Merckx as cycling’s biggest ever star will affect the sport and the Tour and whether the yellow jerseys Armstrong took back to his Texas home should go to other competitors.

The answer there should be “non.” Let the titles remain vacant — a black hole in the record books for the black hole in the 1990s and 2000s that many riders, presumably now including Armstrong, stared into — realizing that the only way they were going to succeed in the drug-addled sport was by pricking themselves with syringes of EPO or swallowing drops of hormones like so many others.

Yes, they were cheats. But there were many victims of the doping culture, too, seemingly including Armstrong, who burned so badly to be more than simply an athletic young kid from a broken home in Plano, Texas.

There will be discussion about the fairness of the process that led USADA to ban Armstrong for life and strip him of nearly everything he won. Some will argue that Armstrong simply tried to protect what’s left of his name and reputation by turning his back on USADA, portraying himself as the victim of what he says is its witch hunt.

And they are already saying that we shouldn’t have allowed ourselves to be sucked in by Armstrong in the first place, because sporting performances that look too good to be true probably are.

That is grossly unfair to all those athletes who don’t dope. And that horrid cynicism kills not only our pleasure in watching sport but the very idea that people can do mind-boggling things.

They can. According to USADA, Armstrong no longer can be said to have won the Tour seven straight times. But we should all fight tooth and nail for the ambition that perhaps one day, someone could and that they could do it clean. Otherwise, why get out of bed in the morning?

Now on holiday in some of the same parts of southern France from where I reported on the Tour, I ask myself where did we go wrong? And did we go wrong?

I remember a journalist once asking Armstrong about the color of his socks and I think, “Should we have asked tougher questions?”

In light of what USADA dug up, yes. But the doping questions were asked over and over and his answers were invariably the same: I train hard, have nothing to hide and how mad would I have to be to pump drugs into a body that barely survived late-stage cancer?

In hindsight, the notion of Armstrong apparently risking his health with doping is one of the most mind-boggling aspects of USADA’s findings.

And during the years he was winning, we were told Armstrong’s drug tests kept coming back negative. Until the evidence started to mount, it was hard to argue otherwise.

There were those, the courageous and enterprising ones, who dug as deep as possible into the growing suspicions that Armstrong wasn’t being completely straight, and a few others who faced his wrath by speaking out.

But the truth is also that witnesses of Armstrong’s apparent cheating didn’t come forward in the same numbers and with the same weight that USADA says they have now.

In short, what we had was Armstrong, with his incredible tale of survival performing incredible feats on a bicycle.

It was good while it lasted. That ride on the Ventoux. The day in the Pyrenees when he snagged his handlebar on a spectator’s bag, fell, picked himself up and rode with fury. On and on. One memory after another.

But it all means absolutely nothing now.

Gone. Didn’t happen.

Mind-boggling.

___

John Leicester is an international sports columnist for The Associated Press.